This semester I am enrolled in a class called Integrated Pest Management, taught by Dr. Luis Cañas at The Ohio State University. One of the first lectures we had was centered around the effects that the environment has on insect populations. As we explored this theme we soon came across the concept of “growing degree days”, and I was reminded of how useful this idea is to increase awareness of what is happening in the natural world around us and to be aware of when potentially damaging insect pests are about to emerge.

Reminded? Yes. At Russell Tree Experts we have been using growing degree days for years now as a tool to help when scheduling our tree wellness services. Seeing the concept again in class made me want to share it with all interested readers.

The concept of growing degree days is based on three basic principles which I will draw from my lecture notes provided by Dr. Cañas:

A “degree day” is the term used for the amount of heat accumulated above a specified base temperature within a 24-hour period.

The base temperature is (ideally) also the “lower temperature threshold”, which is the temperature below which a certain insect will not grow or develop. This is determined by research.

“Cumulative degree days” are just that: the number of degree days that have built up since a certain starting point (in general, since the beginning of the year).

What does this mean for living creatures? This is where things get interesting, so I’m glad you’ve read this far. Have you ever wondered how an insect knows it is time to hatch, or lay eggs, or go into pupation, or finish pupation so it can emerge as an adult? Is it increasing hours of daytime as days get longer after winter? (Maybe, but not quite directly). Is there some sort of internal clock that is ticking that just tells insects when to go into the next stage of development or propagation? But what if that clock went out of sync with environmental conditions? If you are reading this, you are very likely in central Ohio. Lovely state that it is, what do all Buckeyes say about the weather in our state? Exactly. Case in point: Here I am on Monday, February the 3rd, and today I was taking off clothes since I dressed for winter in the morning and got ambushed by 60 degrees and sunny. But the forecast looks like snow by Wednesday.

So what is it? Well, people devoted to these questions looked into it and found that apparently it is the accumulation of heat over time that causes insect development to proceed in synchrony with environmental conditions. So for a given insect, development will begin and continue above a certain temperature (low temperature threshold). Once so many degree days have accumulated (again, specific to the insect type), an egg will hatch, or an adult will emerge, or a nymph will grow into a more advanced stage, for example. These numbers can be identified for insects by watching and measuring. One simple formula (there are others that are more complicated) for tracking degree days is like this:

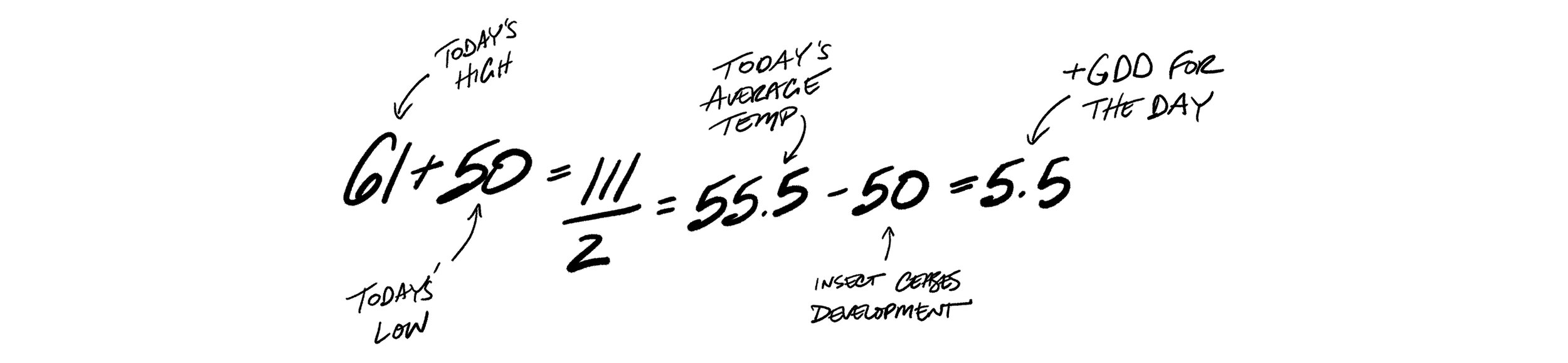

Starting on January 1st, the low temperature and the high temperature within that 24-hour period are logged. Those two temperatures are averaged, and the base temperature (low temperature threshold) is subtracted from the total.

For example: The high today was 61. The low was 50. 61+50= 111. 111/2 = 55.5, the average temperature. Let’s assume a certain insect, we can call it “Steve”, ceases all development when temperatures drop below 50 degrees. We would subtract 50 from 55.5, resulting in 5.5 degree days for today, February 3rd. Note that this number is only accurate for my specific area, since highs and lows are different throughout the state. This is another advantage of this system: It allows us to track Steve’s development in our own back yard!

Continuing with our friend, research has shown that Steve will emerge from pupation as a feeding adult after the accumulation of say, 548 cumulative degree days. What we would do is track degree days every day until we reach at least 548. After we reach that amount we would expect to start seeing Steves show up in our back yard on whatever plants Steves like to hang out on, doing whatever it is Steves like to do when they show up. The neat thing about this is that if we have a cold snap that lasts 3 weeks, even after two days of t-shirt weather in February (which is quite normal for Ohio right?), Steve’s development will simply pause, since degree day accumulation will slow down dramatically during the cold snap. Any day that there is at least 1 degree day, Steve will continue to develop, albeit much more slowly than if there were 20 degree days added on a given calendar date.

If you take the time to think this through you will start to connect all kinds of dots together that will make you marvel at the intricacy of our natural world, and how interconnected everything is. Nothing short of miraculous.

We’re almost done. One more tidbit: Plants seem to follow a similar pattern. This is not only neat, but useful! Since plants also follow this pattern it is only to be expected that certain plants will be at certain stages in their development each spring when Steve is at certain stages of his development each spring. So let’s say it just so happens that my Purple Robe Black Locust is starting to get all dressed up in her pink party dress at around 548 cumulative growing degree days, and that just happens to be the same amount of degree days that Steve needs to finish pupating and emerge as an adult. Instead of calculating degree days to watch for Steve, I can simply keep my eyes on my flowering tree. When I see her in full bloom I know that Steve is also out and about. In this case we call my Black Locust a “phenological indicator”. Her blooming is an outward sign of development in a plant that coincides with an important stage of insect development, thus serving as an indicator for that insect life stage.

The Ohio State University is full of very hard working citizens who study these things. Not only that, they track these things for us and give us a handy tool that does all the calculations (more complex versions than the basic one I shared) and tabulates events at the same time. Check out the resource here: https://www.oardc.ohio-state.edu/gdd/. Delve into it a bit. If you did not know about degree days and how they affect plants and insects, you will be amazed, if you are interested in the outdoors. If you already knew about these things before reading this article, I hope reading this made the concept a bit more accessible. Maybe now you can readily expound on the topic at the next ice cream social you are invited to. Be careful though- you would not want it to be your last. In any case, I am fairly certain you will not find a Steve on the OSU website I gave you above. Steves are not considered to be plant or tree pests so they have not been studied by our worthy scientists.

As always, thank you for reading. I am humbled by all the support I get from my readers. I have had the pleasure of conversing with many of you over the years and count myself blessed because of it.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.