Are Hickory nuts better than Pecans?

Are Hickory nuts better than Pecans? A Journey by T.J. Nagel

We have six native species of Hickory in Ohio: Bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis), Pignut hickory (Carya glabra), Red hickory (Carya ovalis), Mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa), Shagbark hickory (Carya ovata) and Shellbark hickory (Carya lacinosa). Some folks believe that Pecan (Carya illinoinensis), another hickory, is also native to the Southwestern portions of Ohio. Others maintain that it has only naturalized. I personally am indifferent.

In any case, I’ve recently become interested in learning more about the subtle differences between these seven species. I want to be able to confidently identify them by their habit, bark, nuts, and buds, regardless of the season. As I have researched and explored the woods for these different trees I have decided that Shellbark Hickory is my favorite. I could elaborate further but the goal of this article is to tell you about Shellbark Hickory pie so I’m going to skip ahead.

Shellbark Hickory (sometimes called Kingnut Hickory) is a slow-growing and long-lived shade tree reaching heights of 70 - 80’ at maturity with a spread of about 40’. In Ohio, I find it naturally in bottomlands and floodplains although I’ve observed it performing well in parks and landscapes as well. It has large, 1 - 2’ long pinnately compound leaves that are dark yellow-green turning a nice golden yellow color in the Fall. The bark is shaggy, almost identical to the bark of its relative, Shagbark hickory, and the two species can be quite difficult to distinguish from one another. The two trees are so similar that I’ve noticed many folks will erroneously refer to their Shellbark Hickory as a Shagbark. I also realized recently that many of the “Shagbark hickory” I have grown up with are in fact Shellbark.

In a nutshell (pun intended), there are 3 subtle differences I use now to be able to tell the Shellbark and Shagbark hickory apart:

A Shellbark hickory leaf generally has 7 leaflets compared to the 5 leaflets of a Shagbark hickory leaf.

The terminal bud of Shellbark hickory is significantly larger than that of Shagbark Hickory

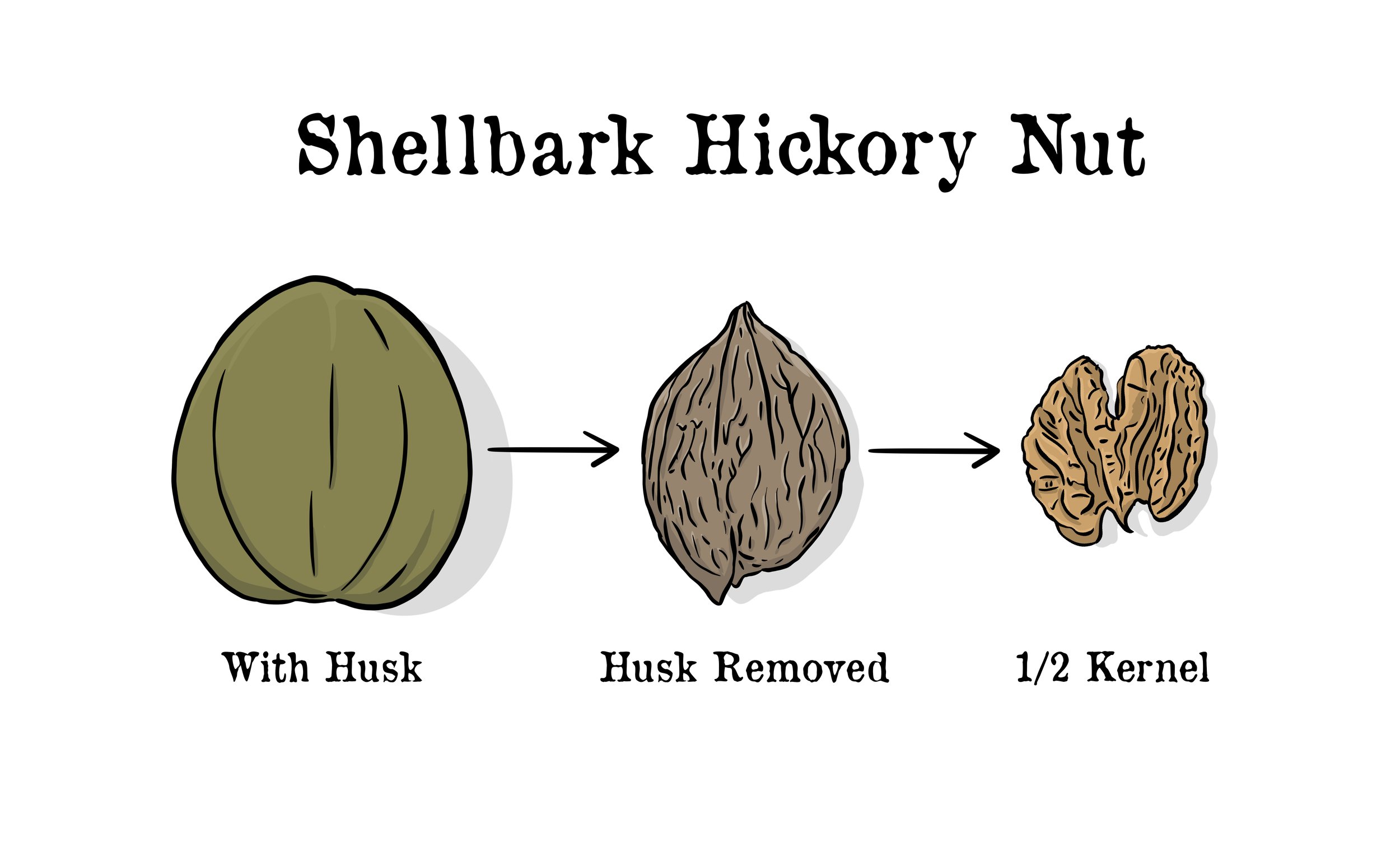

The nut of Shellbark hickory is also much larger than Shagbark, measuring 2 ½ - 3” in diameter compared to the 1 ½ inch diameter of Shagbark.

A few more interesting facts: Shellbark hickory is also a great tree for wildlife. The nuts are sweet and edible and are relished by deer, fox, rabbit, squirrel, wild turkey, ducks, and bears. Interesting side note: my dogs also love Shellbark hickory nuts. The flowers, although inconspicuous, provide nutrition for bees in the Spring as well. And historically, early settlers used Shellbark hickory nuts as a source of food as well as the tree itself for making furniture, tool handles, lumber, and fuelwood. This reminded me of the history of the American chestnut and really got me excited.

My girls this summer at the site of my best producing Shellbark hickory - note all the nuts ready for harvest in the driveway.

As I read more and spoke with more people about the merits of Shellbark hickory, I found that a lot of folks preferred this nut over the flavor of pecan. Some even claimed that Shellbark hickory was a far superior nut and that Pecan had become famous only because it has a thinner husk and thinner shell and is an easier nut to clean. Now, this is a bold statement. Folks in Texas might even consider these fighting words. I knew that I needed to form my own opinion. I decided I would make Shellbark Hickory pie for Thanksgiving.

This pie-making project started with identifying a stand of Shellbark hickory in the woods near my office in Westerville. Between mid-August and mid-October, my father, dogs and I made several weekend trips to this stand of trees to collect Shellbark hickory nuts. Most of the nuts we collected from the ground but some we picked from the trees with a pole pruner. Over the course of 2 months, we collected approximately 20 gallons of Shellbark hickory nuts. This coincided with paw paw season (Asimina triloba) which made our walks in the woods even more rewarding (next year I’m making paw paw hickory pie).

By mid-October Dad and I knew we would need to start cleaning our bounty if we were to have pies by Thanksgiving. The art of cleaning Hickory nuts by hand is a slow art and rushing will only ensure that you eat lots of shells.

Our Hickory nut cleaning process was simple - Dad used a screwdriver and a hammer to remove the hickory nuts from the husk and I used the Cadillac of nutcrackers I purchased on Amazon to crack the shells. From here we used pliers, vice grips, and even dental tools to get the kernel (the edible part of the nut) out of the grooves and different crevices of the shell. We spent 3 separate weekends perfecting our nut-cracking skills and in hindsight, I wish I had kept time so I could compare our speed to next year. The process was at least as long as three OSU games and the entire Cat Stevens discography.

Approximately one-third of our hickory nut kernels were either dried up, infested with weevil larvae, or rotten. These went to the compost. Most of the remaining kernels went into a couple of mason jars and were placed in the freezer until we had time to bake. Anything questionable was set aside for the squirrels. From our original 20 gallons of nuts, we scored about 6 cups of edible Shellbark hickory kernels. This would be enough to make 4 pies.

The following is my recipe for Shellbark hickory pie:

On Thanksgiving day I arrived at my inlaw’s table with two freshly baked Shellbark Hickory pies. I was delighted to see that my sister-in-law had also brought a homemade Pecan pie. I realized that this was the moment I had been waiting for. Today all my questions would be answered. After two helpings of the usual thanksgiving fixings, I made my way to the dessert table and cut myself two equal-sized pieces of pie. One Shellbark Hickory and one Pecan. I covered both with equal amounts of whipping cream and returned to the table. First I had a bite of Pecan. I chewed it slowly and swallowed and then took a sip of water to cleanse my palate. Then I had a bite of Shellbark Hickory. Rinse and repeat a dozen or so times and here are my final thoughts.

I like pie

My sister-in-law’s Pecan pie was prettier than my Shellbark hickory pie with all of the perfectly formed pecans laid out on the surface in a perfect basket weave configuration.

Despite our best efforts, the Shellbark Hickory pie had more shell pieces in it than the Pecan pie.

The flavor of the Shellbark Hickory Pie and Pecan pie was very similar - so much so that most folks would probably not be able to distinguish one from the other if they were not eating them simultaneously.

I think I preferred the flavor of the Shellbark hickory pie but I could be biased after everything we've been through together.

Pecan pie was a delicious and worthy opponent and I mean no disrespect to my sister-in-law or her pie-making abilities.

In all seriousness, I think what really makes Shellbark Hickory superior to Pecan for me is its local proximity (to me), having a knowledge of and a relationship with the trees that the nuts have come from, and all of the memories of my father and I together picking them.

I am in the early stages of my Hickory infatuation and still have lots to learn. If any of you possess any hickory stories, fun facts, or recipes please share them with all of us - you can do so at the bottom of this article. I have one last interesting Hickory side note to share:

I randomly stopped at Watts Restaurant in Utica, OH this Fall while working in the area. If you haven’t had the pleasure of dining there, I encourage you to do so. Watts restaurant is a staple in the Utica community. It has been around for over a hundred years and survived two pandemics so they must be doing something right. They make a number of tasty and authentic family-style country recipes and serve a number of home-baked goods including Hickory nut pie. I bought a Hickory nut pie from them to take home and decided within a couple of bites that it was better than mine. I decided I would go back to Watts Restaurant and ask more questions. I wanted to know primarily (1) what species of hickory they were using in their pie and (2) where were they sourcing their hickory nuts. Might they be from local trees or were they buying them from a faraway land?

When I returned to Watts recently to ask about their Hickory nut pie I discovered that most of their baked goods are actually brought in from Hershberger’s Bake Shop, an Amish wholesale bakery in Danville, OH. For the record, Watts Restaurant does make all of its own cream pies in-house and they are equally delicious! But I still had unanswered questions so I decided to drive to Danville and make a visit to Hershberger’s Bake Shop.

I arrived at Hershberger’s Bake Shop on a cold afternoon this week but received a warm welcome from Naomi Hershberger and two of her colleagues who definitely were not expecting to see a Russell Tree Experts truck come down their driveway. I shared with them my love of Hickory trees and affinity for Hickory pie and that I had happened across their Hickory pie in Utica and that it was better than mine. They were patient with me and answered all of my questions and this is what I learned:

The Hershberger’s are far better at baking delicious pies than tree identification and had no idea what species of hickory nut they were using in their Hickory nut pie (after careful dissection I believe it is a mix of Shagbark and Shellbark).

The hickory nuts are collected locally from native trees in Knox and Holmes counties, Ohio.

They make Hickory nut pie most of the year.

They deliver new pies to Watts Restaurant in Utica every Tuesday and Friday but only a couple of Hickory nut pies each time.

So if you want to try Hickory pie but don’t have time to collect and clean the nuts make a trip this Winter to Watts Restaurant, 77 S. Main St. Utica, OH 43080. I recommend the chicken and noodles over mashed potatoes and a Hickory nut pie to go.

TJ Nagel | Scheduling Production Manager, Russell Tree Experts

ISA Board Certified Master Arborist® OH-6298A // Graduated from The Ohio State University in 2012, Earned B.S. in Agriculture with a major in Landscape Horticulture and minor in Entomology // Tree Risk Assessment Qualified (TRAQ) // Russell Tree Experts Arborist Since 2010

Lecanium Scale (Part One)

If “Lecanium” is a new word for you, consider yourself lucky, or at worst, blissfully ignorant. If you have experienced species of this genus in your landscape you may know how devastating, unsightly, and generally… uncomfortable this insect can be. If you have ever stood under a tree covered in a scale population which is actively feeding and digesting you will know why the word “uncomfortable” came to mind. In this installment I will briefly describe Lecanium scale and its life cycle. In the next installment, I will share an unusual finding from last season, and stand out on a limb to make a forecast for this season.

A Brief Description of a Common Pest:

If “Lecanium” is a new word for you, consider yourself lucky, or at worst, blissfully ignorant. If you have experienced species of this genus in your landscape you may know how devastating, unsightly, and generally… uncomfortable this insect can be. If you have ever stood under a tree covered in a scale population which is actively feeding and digesting you will know why the word “uncomfortable” came to mind. In this installment I will briefly describe Lecanium scale and its life cycle. In the next installment, I will share an unusual finding from last season, and stand out on a limb to make a forecast for this season.

Lecanium is a genus in the family Coccidae. Within this genus there are many different species of scale insects, but fortunately they are very similar in their appearance, feeding habits, and life cycle. This helps arborists identify the insect when populations reach a threatening level on a plant. Because the life cycle is similar from one species to another (with very few exceptions), treatment intervention is relatively straightforward. For the purpose of this article, and for discussion among arborists, we lump these scale species into a generic type we call lecanium scale.

Lecanium scale starts life as an egg. In central Ohio egg hatch usually takes place in June, when Washington hawthorn is blooming. (This event is a phenological indicator for lecanium scale hatch. For more on that topic, read my article here). The first nymphal form (called an instar) is the most mobile state within the lifecycle of the insect. Because of this we call this form a crawler. Crawlers will move out onto the leaf of a plant or tree and affix themselves adjacent to the veins of the leaf where they will feed through the summer. Sometime in late summer these crawlers turn into the second-instar form, and they move back onto the twigs to overwinter. Here one must pause for a moment of silence and ponder the question: How do these nymphs know that their host’s leaves are going to fall off for the winter? Do they really “know” at all? Why do they do what they do?

Female lecanium scale

Moving on, we find these second-instar nymphs waking up with the rest of the plant and insect world the following spring. They begin to feed on the twigs now, and are no longer mobile. A waxy covering begins to form over their bodies as they grow. Most of the lecanium scales will have a domed appearance, some flatter than others, some with different colors, but easily recognizable as lecanium scales once you know what to look for. When the adult female matures, she lays her clutch of eggs underneath her “shell” and dies soon after. The eggs hatch soon and the cycle continues.

Now some comments to finish up the picture:

Many plant hosts are targeted by this insect, including oak, hickory, honeylocust, crabapple, cherry, pear.

There is only one generation per year, which greatly simplifies the treatment process.

The crawler stage is the most vulnerable to treatment and is the one we try to target for control.

The most damaging stage is the second-instar nymph which feeds voraciously on plant sap in order to grow into an adult and lay eggs.

During this stage, digested sap is excreted as honeydew, a sweet substance that coats leaves, sidewalks, cars, and yes, people if you stand under the tree for too long. This honeydew is fed upon by sooty mold, turning the surfaces black.

Large populations can weaken a plant, causing dieback, stress, and even plant death due to the amount of sap extracted during feeding. Sooty mold interferes with photosynthesis, further stressing plants.

How new scale populations arrive onto formerly uninfested trees seems to be a bit of a mystery.

Lecanium scales are grouped with sucking insects (as opposed to chewing insects). They insert a proboscis into plant tissue to feed on sugars and other nutrients in the sap.

So much for the entomology lesson. Congratulations to you stalwart readers who have made it this far! You now have a good base of knowledge that will help you understand how I came to certain conclusions about the 2020 population of this pest, and what this might mean for 2021. I hope you can meet me here once more next week for the final installment!

>> (2/15/21 Update: Read Part 2!) <<

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

[Some technical notes retrieved, and some fact-checking facilitated by W. T. Johnson and H. H. Lyon, Insects That Feed On Trees and Shrubs, Second Edition, Cornell University, 1991.]

10 Trees with Amazing Fall Color... and One You Should Avoid!

I was recently pruning trees in a newer neighborhood on the east side of Columbus where every house had two red maple in the front yard. Although Red maple is a native tree to Ohio, this subdivision was planted with a cultivated variety of the species called ‘Red Sunset.’ ‘Red Sunset’ red maple was selected and well marketed for its compact habit, good branching structure and most notably for its showy and reliable orange to red fall color.

10 trees with amazing fall color

By TJ Nagel

I was recently pruning trees in a newer neighborhood on the east side of Columbus where every house had two red maple in the front yard. Although Red maple is a native tree to Ohio, this subdivision was planted with a cultivated variety of the species called ‘Red Sunset.’ ‘Red Sunset’ red maple was selected and well marketed for its compact habit, good branching structure and most notably for its showy and reliable orange to red fall color.

Unfortunately for most of us in the central Ohio area, ‘Red Sunset’ Red maple was selected in Oregon and requires an acid soil with consistent moisture to perform well. It does not like the dry and often high pH soils of our urban landscapes.

The trees I observed on the East side of town had just been planted in the last 12-15 years, were in poor health & vigor and were already expressing advanced symptoms of chlorosis, a nutrition deficiency that causes yellowing, stunted growth, decline and eventual plant death.

Chlorosis in a Red Maple

I learned about chlorosis in different Red maple cultivars (short for cultivated varieties) when I was a horticulture student at OSU and I still deal with it daily in my career as an arborist. I see chlorotic Red maple in parks, commercial buildings, along streets and in private gardens every day. I even see chlorotic red maple in the aisles of reputable nurseries.

How has this tree become so popular? I believe it’s because it has been so well marketed. Maple has name recognition amongst most folks and the nursery industry loves red maple because it is easy to propagate, and they can produce a sellable tree from small whip in a short amount of time.

When I have the opportunity to ask clients why they selected this tree for their landscape I generally get one the following responses.

Somewhat common: Name recognition, they admit they don’t know much about trees, but they remember maple being a good tree from their childhood.

More common: Their landscaper recommended it (interesting side note: I have yet to hear from anyone that their arborist recommended it).

Most common: They were looking for something with nice fall color.

I’m a sucker for some nice fall color also and I’m here to report there are a lot of other great alternatives to red maple when looking for trees with nice fall foliage. The following are some of my favorite fall color trees that are adaptable, urban tolerant, and easy to grow.

Valley Forge American Elm

Great fast-growing historic shade tree adaptable to most soil types – reliable yellow to gold fall color.

Japanese Zelkova

Another urban tolerant medium to fast growing shade tree with nice vase shaped canopy with yellow to apricot to red fall color.

Black Tupelo

Excellent tree for glossy red fall color. Some cultivars will color yellow and red. Slow growing medium sized tree.

Hickory

This image is of a Pignut hickory but most species of hickory color beautifully in the fall. Slow growing tree. Plant this one for the next generation. Great tree for wildlife.

Sassafrass

Medium sized fast-growing tree in youth. Great yellow to orange to red to purple fall color – can be variable from year to year. One of Ohio’s most outstanding native trees for fall foliage.

Witch Hazel

There are dozens of cultivars of witch-hazel. Most of them have showy fall color. This image is the fall foliage of ‘Diane’ witch-hazel, one of my favorites. Also has showy red flowers in late winter.

Kousa dogwood

Great ornamental tree with exceptional yellow to red fall color. Also has great flowering show, beautiful bark at maturity and interesting fruit.

Ginkgo

Unrivaled for golden yellow fall color. My only complaint is that the show is short lived, often only 2 – 3 days.

Dawn Redwood

Foliage turns an excellent copper orange to brown before leaf drop. Fast growing, significant pest and disease-free shade tree.

Japanese Katsura

Medium to fast growing shade tree. Fall color can be apricot to scarlet red. Fall leaves smell like cotton candy.

TJ Nagel | Production Manager, Russell Tree Experts

ISA Certified Arborist® OH-6298A // Graduated from The Ohio State University in 2012, Earned B.S. in Agriculture with a major in Landscape Horticulture and minor in Entomology // Tree Risk Assessment Qualified (TRAQ) // Russell Tree Experts Arborist Since 2010

[images courtesy of various providers]

Fall Webworm In Full Effect

We’ve received a high volume of calls over the last couple of weeks about “bagworms” in client’s trees. In central Ohio, true bagworm feeds predominantly on evergreens - arborvitae, spruce, and junipers although some deciduous trees can be hosts as well. Generally, this

Fall Webworm vs. Bagworm

We’ve received a high volume of calls over the last couple of weeks about “bagworms” in client’s trees. In central Ohio, true bagworm feeds predominantly on evergreens - arborvitae, spruce, and junipers although some deciduous trees can be hosts as well. Generally, this feeding occurs late Spring through mid-Summer and by mid-August they have stopped feeding to go pupate and become a moth. So I initially was confused about this late population of “bagworm” that had taken central Ohio by surprise and was making my appointment schedule grow faster than kudzu.

After visiting with a few customers, I realized the real culprit of concern was actually, Fall Webworm - not Bagworm. It’s easy to understand why a lot of folks call this pest (which resembles a bunch of worms in a bag) bagworm. This article should clear this up. (For information on true bagworm see the postscript at the end of this post). For those of you reading this article, I hope you can help me to rise up and start a movement to correct this awful error in nomenclature. 😉

The Facts about Fall Webworm

Fall webworm on Bald cypress

Fall webworm is a native pest of shade trees and ornamentals and can appear early summer through early fall. It feeds on over 100 different species of trees commonly attacking hickory, walnut, elm, birch, cherry, and willow. In urban landscapes, I’ve observed it daily on oak, sweetgum, redbud, linden, mulberry, and crabapple.

Fall webworm gets most folks attention by the large unattractive webbed nests it makes at the ends of branches. In most cases, Fall webworm is most damaging to plants aesthetically, diminishing the beauty of its host plant. A large nest can contain dozens to hundreds of caterpillars and can measure up to 3 feet across. Even after caterpillars have left to pupate, empty webbed nests can persist for months containing dried up leaf fragments and lots of caterpillar feces.

A fall webworm feed generally lasts for 5 - 6 weeks before the caterpillar leaves its host plant to pupate in the soil. Fall webworm generally has 2 generations per year.

Fall Webworm Management

Because Fall webworm generally causes little to no harm to the overall health of established healthy trees, I generally do not recommend management for this pest. Ohio has dozens of natural predators that make a living on Fall webworm including several species of birds, parasitic wasps, and other beneficial insects and they can generally keep populations of Fall webworm in check without the help of human intervention.

Newly planted trees could be at risk of significant defoliation and heavy feeding could impact fruit or nut yield for crop trees. If management of Fall webworm does become necessary, nests can be pruned out and destroyed or insecticides can be sprayed to kill the caterpillars while they are feeding. The beneficial bacteria "Bt" (Bacillus thurngiensis) can also be used on young caterpillars. This is available at most high-end garden centers labeled as Dipel or Thuricide.

If spraying is your control method of choice, please note that product only needs to be applied directly to the nests (rather than the entire tree) to avoid damage to beneficial insects and other non-target organisms.

If you need assistance managing Fall webworm - we’re here to help.

And Now, Bagworms

Bagworm is a small caterpillar that uses silk and bits of foliage and bark from its host plant to make a small bag around its body to protect itself. Each bagworm has its own individual bag (which often resembles a small pine cone), rather than large webbed nests that protect entire communities of caterpillars like in the case of Fall webworm. Bagworms feed aggressively from late May through July and can quickly defoliate entire portions of trees and shrubs if left unchecked.

Bagworms can be removed from plants by hand and disposed of easily on small trees and shrubs. On larger plants, insecticide applications can be made effectively through June before bagworms have covered their bodies with their bag.

Thanks for reading!

TJ Nagel

ISA CERTFIED ARBORIST® OH-6298A