♥ Happy Valentine's Day! ♥

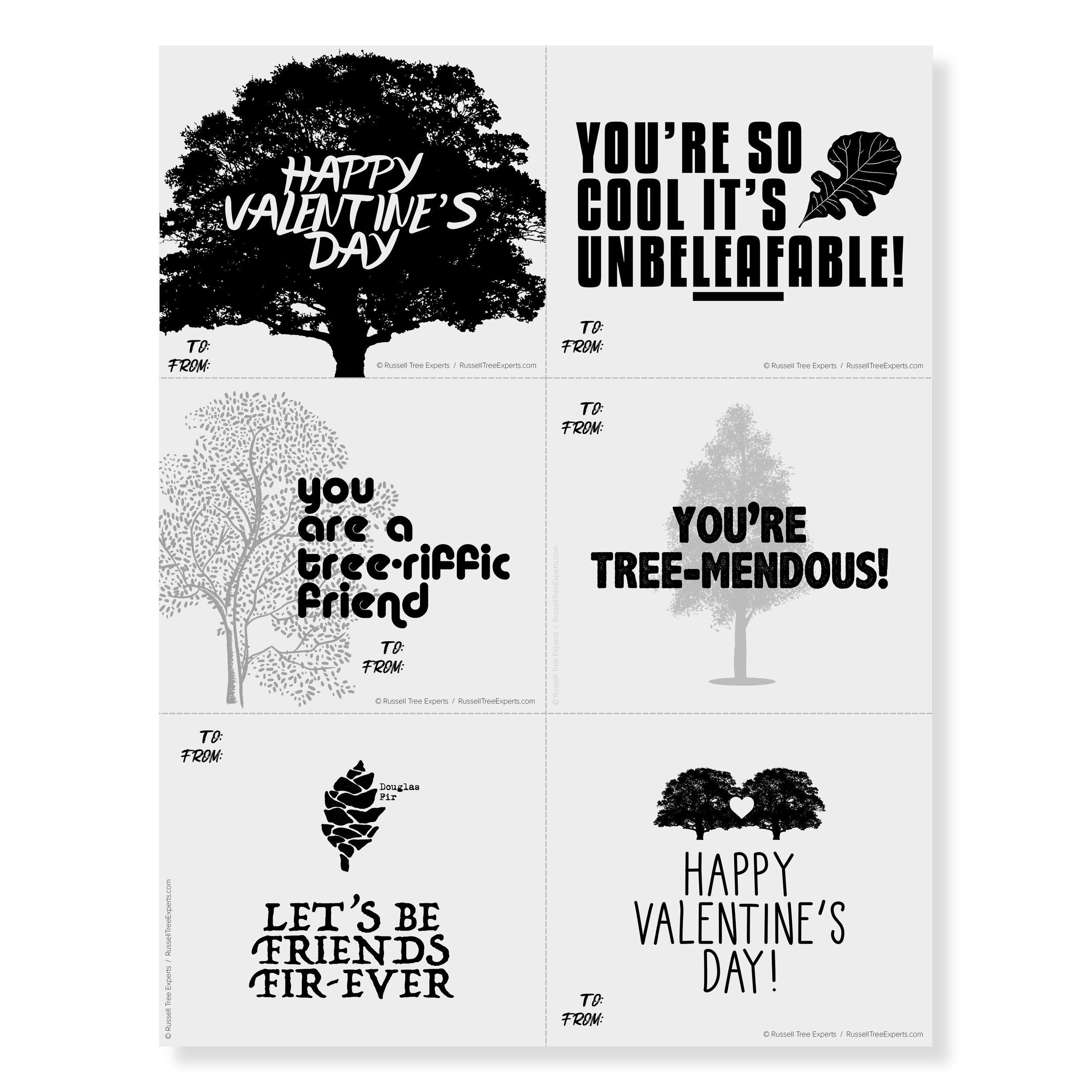

Don’t you miss handing out Valentine’s Day cards at school? Did you make the shoe box and hope to get a card from that special someone? We’re feeling a little nostalgic this year so we decided to create some tree-inspired mini Valentine’s Day cards. You may not be in grade school anymore but take a moment and feel like a kid again by printing our Valentine’s Day cards below and give ‘em to your special someone!

Don’t you miss handing out Valentine’s Day cards at school? Did you decorate the shoe box and hope to get a card from that special someone? Or were just hoping for candy? Well anyway, we’re feeling a little nostalgic this year so we decided to create some tree-inspired mini Valentine’s Day cards for adults and the kiddos!

To get started:

Click on the below sheet for which you wish to print

Print the file

Cut on the dotted lines

Fold the cards down the middle (if indicated)

Write your special note

Present the card(s) to your valentine(s)!

Happy Valentine’s Day, everyone! We hope you’re staying healthy and having fun!

Sincerely,

Kenny Greer | Marketing Director, Russell Tree Experts

Kenny graduated from The Ohio State University with a BFA in Photography. He enjoys photography, graphic design, improv comedy, movies (except for the scary ones), and spending time with his wife and 2 kids.

Where’s the Fruit?

As an arborist, I often feel like I need to double as a detective. Trees, obviously, cannot tell us verbally how they are "feeling" or why they are behaving in a certain way. We have to look for clues as to what is possibly going on with them. When I am asked why a tree is performing poorly, oftentimes I need to swap out my helmet for a Sherlock Holmes cap and start digging around, asking questions of the tree's caretaker and standing back to observe the environment in which the tree exists.

As an arborist, I often feel like I need to double as a detective. Trees, obviously, cannot tell us verbally how they are "feeling" or why they are behaving in a certain way. We have to look for clues as to what is possibly going on with them. When I am asked why a tree is performing poorly, oftentimes I need to swap out my helmet for a Sherlock Holmes cap and start digging around, asking questions of the tree's caretaker and standing back to observe the environment in which the tree exists.

One of the questions I am asked often, especially this past year, is "why didn't (or doesn't) my fruit tree produce fruit?" The answer to this can be complicated and can have many explanations. The fruit trees we typically grow here in Ohio are apples, pears, peaches, nectarines, cherries, and plums. These trees are all in the same rather challenging plant family, the rose family or Rosaceae. This family of trees (and shrubs) is susceptible to many pests, diseases, and seasonal issues. The biggest culprit last year was a late spring freeze near Mother's day [See Fig. 1]. This polar vortex sent Ohio orchard owners scrambling to save their precious buds, flowers, and very young fruit. There was also a freeze in mid-April that killed a lot of the very early blooming flowers of peaches especially.

[Fig. 1] Temperatures dipped below and to freezing on May 9th and 12th in 2020.

Cold is a component that is very important to fruit production. Fruit trees need a certain amount of "chill hours" below a given temperature to recognize that winter has occurred and that it is time to wake up and flower. Typically, here in Ohio, we get plenty of chill hours. Our issue is either extreme and prolonged cold or a very cold dip in temperature after a warm, late winter spell. Very cold winters can kill dormant flower buds and even entire trees. This may be the case if your tree does not flower as expected in the spring. In the case of warm periods before a freeze, the tree may flower beautifully, but the flowers are damaged and cannot create that yummy crop you had been dreaming of.

Apples and pears are the most cold-hardy of the rose family fruit trees and produce fruit most reliably in our climate.

Windy, rainy, and chilly weather in spring also presents an obstacle for some of our tiniest workers, the pollinators. Native bees, honey bees, and bumblebees need to be present if any fruit is to develop on your tree at all. However, these gals are reluctant to venture out in search of pollen if the weather is wet and gusty and the temperature is below 55 degrees Fahrenheit. Thank goodness each flower is viable for 3-4 days and flowers do not open all at once. If the sun comes out for even one nice afternoon, you should have some pollination even in the worst weathered spring. Attracting bees to your yard with bee-friendly perennials and reducing the use of insecticides while bees are active should also help your future yields.

Along with pollinators, many fruit trees need a pollinizer as well. Peaches, tart cherries, nectarines, and some plums are self-fertile and will produce a crop without the help of another tree. However, apples, pears, and sweet cherries need a second tree of the same species, but a different variety, to cross-pollinate with. The trees should have overlapping bloom times and be within 300 feet of each other to be the most successful. It is interesting to note that crabapples are the exact same species as apples and will pollinate apple trees as long as they flower at the same time (and the crabapple is not a sterile variety). It is also interesting to note that cross-pollination between different varieties does not change the nature of the fruit. A Red Delicious apple tree will always produce Red Delicious apples even when pollinated by a Snowdrift crabapple [See Fig. 2], but if the seeds from the cross-pollination are planted, an entirely different and surprising fruit may be produced.

[Fig. 2] A Red Delicious tree pollinated by a Snowdrift Crabapple will still produce a Red Delicious apple.

So, if you had good fruit-producing weather during winter and spring, saw many bees working your full bloom flowers, and are sure you have a pollinizer nearby, we will have to look for more clues.

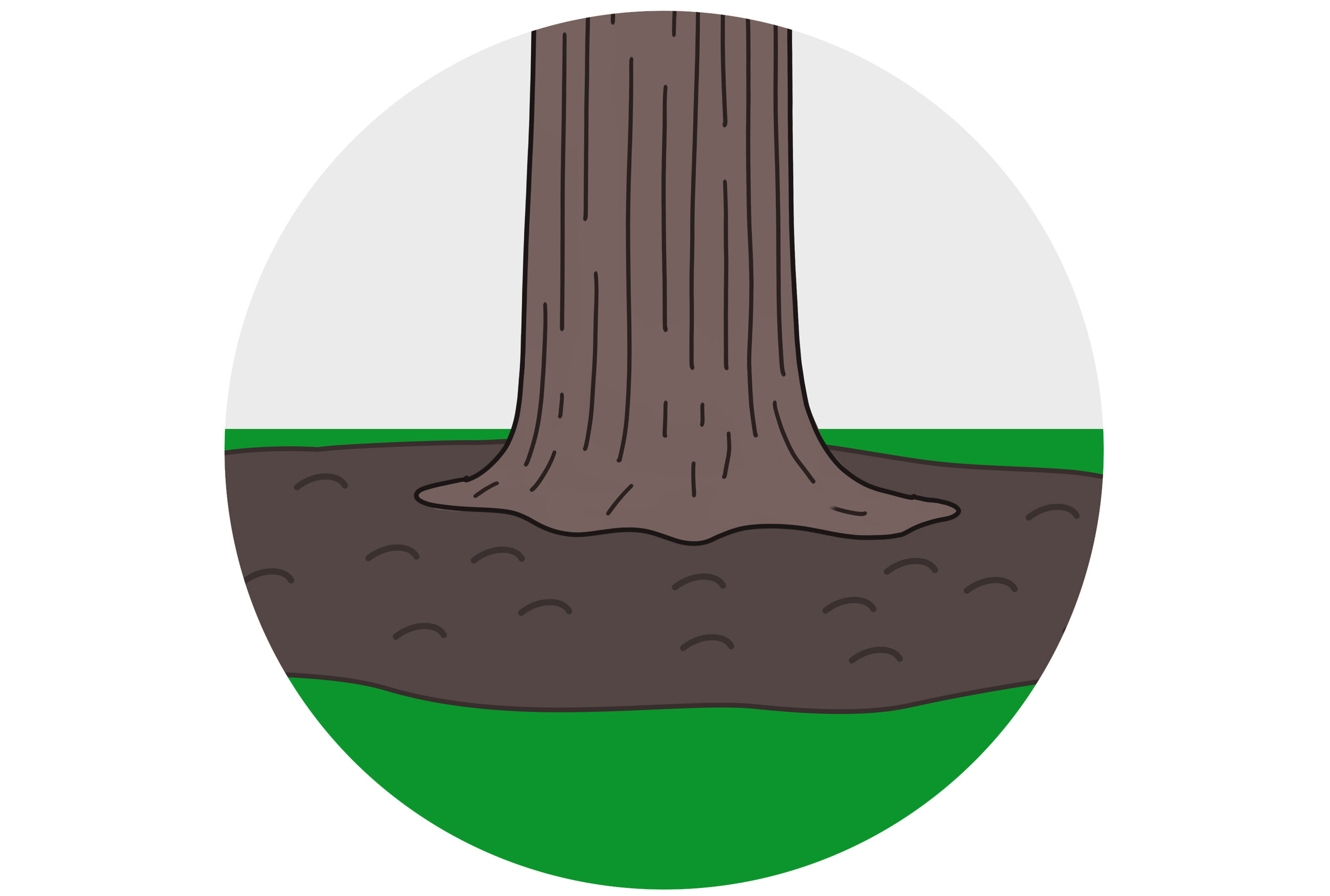

[Fig. 3] The dripline of a tree

Is your tree getting enough sun?

Fruit trees have the best yields with at least 8 hours of sun a day.How old is your tree?

Most fruit trees need to be between 3-5 years old before they flower and set fruit.Is your tree starved for nutrients or has it been fertilized too much?

Producing flowers and fruit takes a lot out of a tree. Fruit trees definitely benefit from a spring application of slow-release organic fertilizer to give them a boost of energy. You can also spread cow manure or compost within the dripline [See Fig. 3] to improve the soil and nourish your tree. On the other hand, over-fertilization with quick-release synthetic fertilizers high in nitrogen will cause your tree to grow too much. This vigorous green growth is at the expense of flower and fruit production and will make your tree more susceptible to fungal and bacterial attack and look delectable to deer and insects.Has your tree been pruned lately?

Pruning fruit trees during the dormant season each year can improve fruit production. It is recommended to remove 25% of the tree’s canopy (depending on age), concentrating on limbs that are broken, dead, crossing, growing into the tree, or growing vertically (water sprouts). Pruning to maintain good air circulation and sun penetration within the tree by making the correct thinning cuts will assist in keeping leaves dry and less susceptible to disease. It is important to note that fruit production is better on more horizontal limbs than limbs that grow more vertically.Is your tree getting enough water during our very hot, dry summers?

Without the proper hydration, fruit will suffer so that the tree itself can survive. Removing turf and weeds within the dripline of your tree and applying a thin 2” layer of organic mulch can help retain moisture and reduce competition. Apply supplemental water slowly and deeply during times of drought.Do you suspect your tree may be infested with insects or infected with a disease?

There are many insects, mites, fungi, and bacteria that love to feast on and infect fruit trees. Dormant oil sprays in late winter and fruit-friendly fungicide sprays during the spring may be needed to produce edible fruit.

If you have a fruit tree that needs pruned, fertilized, or inspected and treated for disease and insects, call Russell Tree Experts and entrust their proper care to our team of certified arborists. We would love to care for your trees and help you get to the bottom of “the mystery of the missing fruit”.

May you have a fruitful year ahead!

Krista Harris | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Krista grew up in the central Ohio area and became an ISA certified arborist in 2017. She graduated from The Ohio State University with a Bachelor of Science in Crop Science and a minor in Plant Pathology in 2000 and has been in the green industry ever since. Her favorite trees are the American sycamore, American beech, and giant sequoia.

BS in Horticulture Crop Science, The Ohio State University

ISA Certified Arborist® OH-6699A

ODA Comm. Pesticide Lic. #148078

CPR & First Aid

Planting Trees for a Purpose

I think we all can agree that our TREE FOR A TREE® program is an awesome idea for replacing the trees that we remove, but as I set in the office watching nature happen outside my window, I started thinking of other reasons to plant trees. Trees provide countless benefits to our environment as well as providing food and shelter for a number of living organisms. Anytime that I am walking through a property I cannot help but notice the birds enjoying all that the trees are providing for them. I decided to write about planting trees that provide shelter and food for birds throughout the year.

I think we all can agree that our TREE FOR A TREE® program is an awesome idea for replacing the trees that we remove, but as I set in the office watching nature happen outside my window, I started thinking of other reasons to plant trees. Trees provide countless benefits to our environment as well as providing food and shelter for a number of living organisms. Anytime that I am walking through a property I cannot help but notice the birds enjoying all that the trees are providing for them. I decided to write about planting trees that provide shelter and food for birds throughout the year.

Eastern Red Cedar

One of the first types of trees that I would consider would be conifers. Not only do they provide fruit and seed throughout the fall and into winter, but they also provide unmatched cover and nesting sites. The Eastern red cedar would be a favorite for our area as well as White pine and many Spruce species. If you plan to feed the birds, it is always a good idea to have conifers nearby to provide cover for the birds taking advantage of your feeders.

The next type that I would recommend planting for attracting and feeding birds would be a variety of fruit trees. Careful selection of varieties can provide fruit throughout the year. One favorite would be the Mulberry tree, but be careful with placement as the fruit can be rather messy. Other smaller trees would be Serviceberries, Flowering Dogwoods, and Crabapples which can provide fruit from the summer, (Serviceberry) to the fall, and even into the winter with many Crabapples.

Of the large native trees, there are a few that seem to attract a large variety of birds, including wild turkeys. Some would be the White oak, Wild black cherry, and the American beech. They provide nuts, fruit, and the Beech often provides hollow nesting sites as well, often used by Owls.

Virginia Creeper

There are also many vines that are very beneficial to birds. A couple of favorites are wild grape vines which are great for the fruit they provide and the shredding bark is great for nest building material. Another would be the Virginia Creeper vine that provides fruit that can last into winter and as a bonus has brilliant fall color.

One thing to keep in mind when planting to attract birds in our area is to try to use native plant material when possible. There is a large variety of native shrubs as well that are awesome plants with a lot of benefits for birds.

Another idea that I observed recently while visiting a client’s property was a technique they used to attract woodpeckers. They gathered large fallen branches from a wooded area on their property and leaned them against a tree outside their window where they hang their bird feeders. The woodpeckers would come to extract insects from the decaying branches.

In closing, I would like to mention a few quick reminders to keep in mind whenever planting trees and shrubs:

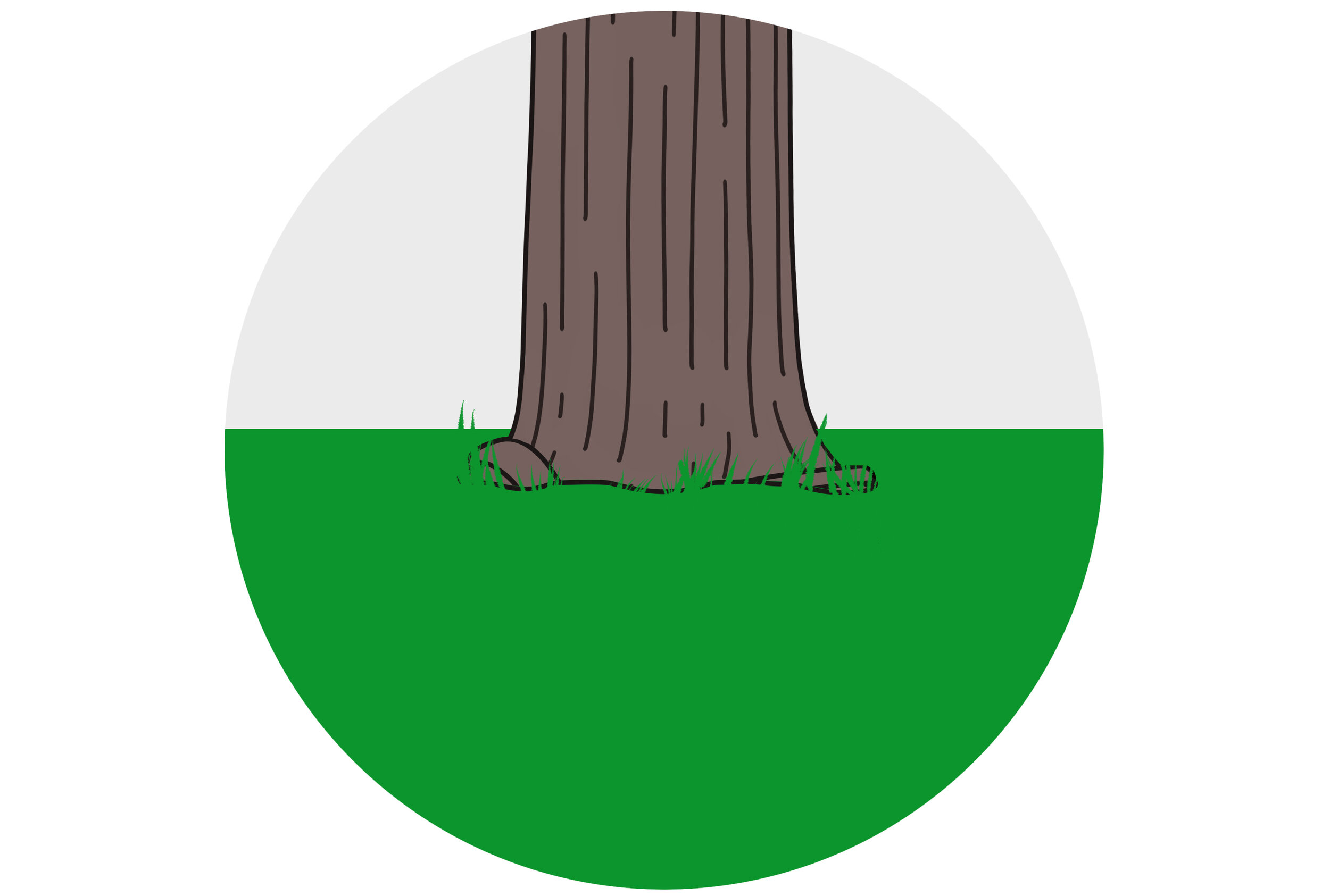

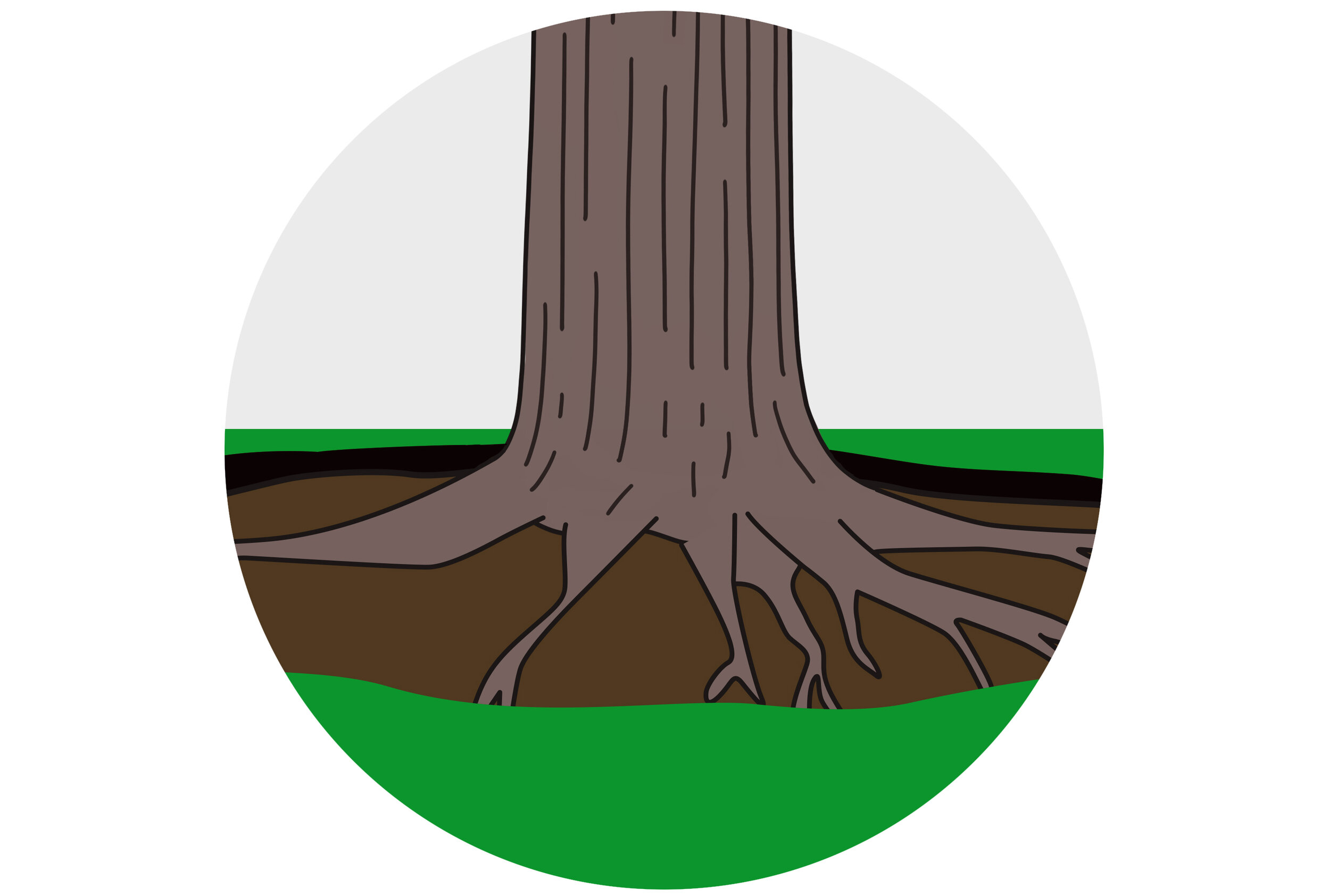

Always identify the root flare on your plant material prior to digging the hole as this will identify how deep to dig the hole.

Dig a broad shallow hole, no deeper than needed to place the root flare at the same height as the surrounding grade, and broad enough to allow proper root expansion.

Firmly backfill around the root ball and only stake when necessary to support the tree.

Water thoroughly and cover the excavated area and tree with 1-2 inches of mulch.

Also, here is a how-to video created by our team. Check it out!

Mike McKee | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Mike graduated from Hocking College in 1983 with a degree in Natural Resources specializing in urban tree care. He has been a certified arborist since 1991. Mike started his career in the private industry in 1985 before becoming a municipal arborist in1989. He retired after serving thirty years before joining us at Russell Tree Experts in Sept. of 2018. His love of trees has never waned since trying to climb up the ridges of the massive Cottonwood tree in front of his childhood home.

Understanding Conifers

Understanding conifers should begin with a few simple definitions to clarify and classify. A conifer is a plant that bears its seeds in cones. When we hear the word cone, we likely think of pine and spruce trees, two types of coniferous trees that are widely found throughout Central Ohio and beyond. Their cones are obvious when they fall and scatter on the ground surrounding the tree. But did you know that yews (Taxus) and junipers are also conifers?

Avocados can be tricky. You buy them green, and the next day they’re still not ripe. The day after that they’re still not ripe. Then, the day after that they’ve all gone bad! To be clear, avocados don’t come from conifers. But I’m often reminded of avocados when homeowners contact us regarding concerns they have about their conifers. Conifers, like ripening avocados, can also be tricky. A row of ‘Emerald Green’ Arborvitae can appear to be fine, and then seemingly overnight, half of them are DEAD! A mature white pine can appear to “almost die” every second or third year. These issues can be understandably frustrating and can give us the false notion that these plants are hard to grow. Understanding the ways in which they’re different from other plants in the landscape can help in successfully caring for conifers and allowing them to thrive.

Understanding conifers should begin with a few simple definitions to clarify and classify. A conifer is a plant that bears its seeds in cones. When we hear the word cone, we likely think of pine and spruce trees, two types of coniferous trees that are widely found throughout Central Ohio and beyond. Their cones are obvious when they fall and scatter on the ground surrounding the tree. But did you know that yews (Taxus) and junipers are also conifers? Both bear their seeds in a fruit-like structure that is often incorrectly referred to as a berry. These berry-like fruits are actually cones, botanically speaking. Some other common conifers in Central Ohio include arborvitae, hemlocks, and firs. Because the foliage of most conifers is evergreen, meaning it does not fall off each year with the cycle of the seasons, the terms evergreen and conifer are often used interchangeably. Doing so, however, is not completely accurate. It’s important to understand that the term evergreen also refers to some broadleaf plants like rhododendron, holly, boxwood, and others. These plants are evergreens, but not conifers.

Conifers belong to a very ancient classification of plants and are different from non-coniferous plants in a number of ways. Below are a few of their key characteristics that often confuse homeowners (and sometimes even otherwise qualified arborists!). Knowing what to expect and how to care for conifers is the first step in successfully maintaining them in your landscape.

Seasonal Needle Drop

Japanese White Pine experiencing fall foliage

Even though most conifers are evergreens, their evergreen foliage still eventually falls off. Some very common conifers in Central Ohio, like pines, yews, and arborvitae, will drop a significant amount of their inner foliage every 2-3 years as part of a natural occurrence of cyclical needle drop. This can be alarming if you’re not familiar with the process. When it happens, the important thing to recognize is that it’s happening uniformly throughout the entire plant, and all of the browning/yellowing foliage is further back on the branch. These are the needles that are 2-3 years old and have reached the end of their life cycle. You might also look around your neighborhood to see if the same tree or shrub in other landscapes is doing the exact same thing, and at the same time. This process will never occur on the tips of the branches. If you have needles that are discoloring and falling off from the very tip or end of the branch, it is likely due to other factors and may indicate a disease, insect, or watering issue.

Delayed Response to Stress

A dead ‘Emerald Green’ Arborvitae due to drought stress

Perhaps the most challenging thing about conifers, specifically evergreen conifers, is that they do not give immediate feedback from water-related stress or injury. Herbaceous annuals like impatiens and petunias will let you know almost immediately when they are low on water by wilting excessively. Many deciduous trees, when first planted, will also show signs of wilting foliage relatively quickly when their roots become dry. This type of visual feedback is often what reminds us to get outside and water our newly installed landscape trees or shrubs. Coniferous evergreens, on the other hand, can have a delay of weeks or even months before they show obvious signs of drought stress. The reason this is an issue is simple; by the time we see it, the damage may be too extensive to reverse. It’s important to thoroughly and properly water any newly planted trees or shrubs. Don’t over-rely on in-ground irrigation, which often does not water for a long enough span of time to properly soak the ground, or may not thoroughly cover an area, leading to “dead zones” that receive little to no water at all. Proper watering regimes should be followed for the first season, and supplemental watering may be beneficial in subsequent years during very dry months. Watering in the fall is important too. This helps to keep roots moist once the ground freezes. Inadequate levels of water in the soil during freezing temperatures can rob a plant’s roots of water and lead to winter desiccation. Oftentimes we see this show up late winter or even early in spring.

Limited Regrowth with Pruning

The proper pruning of conifers varies from that of their non-coniferous counterparts. Many landscape shrubs and even a few tree species can be pruned aggressively to maintain a certain size or habit without adversely affecting the health and longevity of the plant. Many conifers, however, are not tolerant of heavy pruning that removes the majority of the foliage from a stem or branch. Junipers provide a classic example of a plant that cannot be pruned back to bare wood. Once this is done, the exposed area will not fill in with new growth. Pine, spruce, and fir are also examples of conifers that will not produce enough new growth on over-pruned parts of the plant. One example of a conifer that is an exception to this rule is the yew. When cut back aggressively, yews can and do generate enough new growth (slowly) on old, bare branches. Knowing how to properly prune conifers requires a good understanding of each plant species’ characteristics and habits, and may be best left to a professional arborist.

Healthy Dawn Redwood trees in the fall

Finally, it’s worth noting that a few types of conifers succeed in inciting worry and confusion whenever a home changes hands and the new owners are unfamiliar with the trees in the landscape. These are of course the deciduous conifers. Two deciduous conifers can be found commonly throughout Central Ohio landscapes- the dawn redwood and bald cypress. These trees will naturally lose their needles every year just like a Maple or Ash loses its leaves. As mentioned previously, most of us equate conifer with evergreen. So to see this occur for the first time and not understand what’s happening, one might assume the tree is dying for some unknown reason.

Conifers do things a bit differently, which can make them a little harder to understand. Answers to your coniferous questions are always just a phone call away at Russell Tree Experts. The unique characteristics mentioned above are just a few of the many reasons you should entrust your trees, all of them, to a qualified professional tree care company. Otherwise, your new neighbor, though his intentions are good, might just tell you to cut down that dawn redwood that keeps “dying” every year.

Walter Reins | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Walter has been an ISA Certified Arborist since 2003. He graduated from Montgomery College in Maryland with a degree in Landscape Horticulture, and has called Columbus, OH his home for nearly 20 years. Walter appreciates trees for their majesty and the critical role they play in our world.

Putting the Year to Sleep

Today the light begins to increase again; days begin to lengthen. For the last 6 months or so each day has lost a minute or two of daylight, growing shorter as this part of the world approached the darkest day of the year. Earlier this week I was reading the musings of Henry David Thoreau once again, and came across a passage about the wonders of a milkweed seed, how each seed is carefully packed within its “light chest” attached to silk streamers, to be released when the time is right. Thoreau ends the thought with a quiet reflection on the faith of a milkweed plant which “matures its seeds” despite the prophecies of some men that the world would end.

[Written on December 22, 2020 @ 7:29 am]

Today the light begins to increase again; days begin to lengthen. For the last 6 months or so each day has lost a minute or two of daylight, growing shorter as this part of the world approached the darkest day of the year. Earlier this week I was reading the musings of Henry David Thoreau once again, and came across a passage about the wonders of a milkweed seed, how each seed is carefully packed within its “light chest” attached to silk streamers, to be released when the time is right. Thoreau ends the thought with a quiet reflection on the faith of a milkweed plant which “matures its seeds” despite the prophecies of some men that the world would end.

I remember as a child when I would help my father clear a new patch of ground to expand the garden. I was always amazed when, a few weeks later, the soil we had stripped of grass and cultivated began to grow all kinds of weeds that had not been there before. Plants that looked different to me from those we had cleared out to make the garden. “The seeds are all there, waiting to grow at the right time,” my father would tell me. Even then the idea of a seed just waiting there to grow, and then eventually deciding in some way that it was time to sprout, to cast off the protective husk and send out a tiny tendril of life, to risk it all in the hope of becoming something totally new, a plant with leaves that could harvest life from the sun – even as a child I remember thinking there was something mysterious about that. And now as an arborist every now and then I will look at an oak tree standing over 100 feet tall, overshadowing several houses in downtown Columbus, its bulk shouldering up between street and sidewalk, offering food and shelter for possibly hundreds of other plant and animal species. All the while the tree is using sunlight as energy to split a water molecule to use the energy stored in those chemical bonds to gather carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in order to make carbohydrate for food and structure. Every now and then I will stop my feet from crunching the acorns under such a tree and think “this tree came from an acorn just like one of these under my feet.” I pick up the acorn and look at it, itself an amazing little package, perfectly formed with characteristics unique to its species. If it is in the white oak family it might already have a tiny white root peeking out of one end if it is late fall. But I hold the acorn in my hand where I can see it against its parent, step back, look from one to another. The tree came from one of these. At some point an acorn was produced, carried to one spot or another by a squirrel, a blue jay, a person. Perhaps the acorn was planted, perhaps it was forgotten. But it bided its time, listening, feeling, sensing somehow. Am I anthropomorphizing? Perhaps. But sensing is sensing no matter how you look at it, and sensing is inextricably linked to purpose.

In time something within the acorn trembles – whatever it is waiting for seems to be happening. Moisture, temperature, sunlight. All coalesce and movement begins somewhere in the heart of the acorn. Energy stored within the seed is being consumed, and suddenly a root tip emerges. A purpose is being fulfilled. A stem peers out, pale and spindly, stretching upward with a mixture of hesitancy and confidence – faith.

Special proteins within the seedling called photoreceptors begin to absorb light, responding to very specific light frequencies that cause these proteins to stimulate change: “Produce chlorophyll”; “Expand leaves”; “You’ve emerged from the soil, straighten out your head”; “Stop extending so much, make some branches”; “Make some other pigments so you don’t burn up in the sun”. And so a tree begins.

Question: What is the difference between a seed and a tree? Once the tree begins, what becomes of the seed? Many of us shy away from words like faith because we link them to “religion,” perhaps fearing that such words lead us away from “science” or “real life.” But if we dared we would see that every day, each of us makes decisions based on nothing more than faith. We park our car in the lot and walk into a store, never wondering if our car will be waiting for us or not when we return. We believe so strongly that it will be there that we would be extremely surprised and upset if it were not.

Many of us go to work knowing that come Friday, we will be paid. We stop at the store on the way home and get some milk, fully expecting to wake up tomorrow hungry for breakfast. We expect to wake up so strongly that we would be surprised if we did not.

We walk into a dark room and feel on the wall for something that we know if we just move it one way or another, light will fill the room.

Perhaps because my work takes me outside more than inside I tend to follow the passing of days more by length of light than by the numbers on a calendar. So when winter solstice arrives here in the Midwestern United States I feel movement somewhere inside my chest. A trembling, of sorts, perhaps similar to a seed that is beginning to stir. Something, in this case, history, tells me more light is coming, and I have no reason not to believe it. In fact, I would be surprised if by the end of December the sunlight was not sticking around for several minutes longer per day than it was yesterday. Longest night is beginning to move once more to longest day. And here is a gift: where there is faith, there is hope.

Most of what I have heard and read in the latter part of 2020 is how difficult this year has been for people all over our world. No need to revisit why. Rather than making resolutions for a new year, I am instead going to plant this past year into the fading darkness like a seed into dark soil. And I have faith that, like a seed, it will become something new, something I had never expected it to be, something that will then bear fruit of its own to be planted yet again.

Somewhere I heard about a farmer who plants seeds in a field and then simply goes to sleep. Why? Because he lives by faith. He knows the seed will sprout and turn into plants that will bear a harvest for food.

I like this story. Who doesn’t like to take naps? But even a good nap is not possible without faith.

I wish you all the best in this coming year.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

How do you become a Certified Arborist?

Have you ever wanted to become a Certified Arborist? The first step is developing an interest in trees: species, habits, ideal growing conditions, diseases, pests, structure, life cycle. An inquisitive mind is a great asset for any arborist. Any question about trees is a good question! Now that your curiosity is piqued, the next step in developing your arboreal skills is finding the answers!

Have you ever wondered what it takes to become a Certified Arborist? The first step is developing an interest in trees: species, habits, ideal growing conditions, diseases, pests, structure, life cycle, and so forth. An inquisitive mind is a great asset for any arborist, and any question about trees is a good question! Now that your curiosity is piqued, the next step in developing your arboreal skills is finding the answers! This can be either formally, in a classroom setting, or informally, from fellow arborists or friends and colleagues, or simply learning as you go along or doing your own research. Developing a good base of tree knowledge is a great tool to have when you are trying to accomplish your goal of becoming a Certified Arborist. We’ve also had plenty of people start working at Russell Tree Experts with only a vague interest in trees or just interested in an environment where you can work outside in the fresh air! Either path is a great start to your journey to becoming a certified arborist.

Once you have some knowledge, what are the next steps? In order to be considered to take the ISA Certified Arborist Exam, you must have at least 3 years of documentable experience in the tree industry; whether this is from a position at Russell Tree Experts or another accredited company or formal education from a College or University. Once this experience is verified, you may submit an application to the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) for them to approve. From there, you can schedule either an in person exam or a computer based exam at a testing facility. You must pass the exam with a 76% or higher to become an ISA Certified Arborist.

During the exam, your knowledge will be tested in the following 10 sections:

Soil Management

Identification and Selection

Installation and Establishment

Safe Work Practices

Tree Biology

Pruning

Diagnosis and Treatment

Urban Forestry

Tree Protection

Tree Risk Management

Once you’ve passed your exam with a 76% or higher, your ISA Certified Arborist certification is valid for three years. To retain this, you must re-certify by either taking the exam again, or earning 30 continuing education units (CEUs) over the course of the three years. You can earn CEUs by attending various conferences with continuing education classes, doing quizzes in monthly Arborist News publications, or signing in and viewing webinars about new or developing tree issues around the country.

I am fortunate to have been able to become an ISA Certified Arborist in 2018 and am glad to have spent my time here at Russell Tree Experts, learning more about trees, every day, than I ever thought possible. This past February I was able to attend the Ohio Tree Care Conference (put on by the Ohio Chapter ISA) and was able to put many faces with many names that I’ve learned over the past few years while earning plenty of CEUs to retain my certification. I feel blessed to have found my tree family and look forward to learning more in the years to come.

Check out isa-arbor.com to learn more about how you can become an ISA Certified Arborist and to apply for your certification visit: ISA Certified Arborist Application Guide

Lindsey Rice | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Lindsey joined Russell Tree Experts in 2015 with a B.S. in Agribusiness and a minor in Horticulture from The Ohio State University. Growing up in Northwest Ohio, she participated in various sports, band, and FFA which ultimately inspired her love for the tree industry. In her free time she loves to spend it outdoors with her husband and daughters.

Free Trees! (Update: ALL GONE!)

We are giving away bundles of tree saplings! Just stop by our office during the times listed below for a contact-free pick up of a bundle of 5 trees plus a "Keep Ohio Green" tote! There are only 100 bundles so get here before they are all gone!WOW! We are blown away by the excitement for these trees! 100 bundles of tree saplings (500 trees in total!) were all picked up within 4 hours! We weren’t expecting them to go THAT quickly!

If you were one of the lucky ones that receive a bundle, please plant the trees AS SOON AS POSSIBLE and check out this video on how to plant! If you weren’t able to get here before all the trees were claimed, keep an eye on your email next spring — we will be doing this again! :)

Thank you all for your support in our mission to KEEP OHIO GREEN and check out TREEFORATREE.com to learn more about our tree planting program!0 BUNDLES REMAINING

(as of 11/19/20 @ 4:15PM)

Pick-Up Location

To pick up your free trees, visit our office (address below) and pull into the front parking lot. The trees will be available on the table in front of our office door. Please only take one bundle per household. Enjoy!

Address:

3427 E Dublin-Granville Rd

Westerville, Ohio

43081Tree TYPES

Each bundle of will include five trees. The species of trees you will receive will vary from bundle to bundle however the trees you could receive are Sycamore, Hackberry, Honeylocust, and/or Sugar Maple. See the below photos to help identify your trees! Please note, these are tree saplings so they are smaller, ranging from 6"-24".How to Plant Your Trees!

STEP 1

Soak your tree sapling in water for 5 to 7 minutes to thoroughly moisten the sapling’s root system.STEP 2

Select your tree planting site. Avoid planting your sapling within 5 to 10 feet of any large obstructions such as mature trees or buildings.STEP 3

Measure the sapling’s base of the root to its root flare to determine the depth of your hole.STEP 4

Dig your hole!STEP 5

Ensure that your hole is of the appropriate depth. To do so, place your sapling in the hole and ensure that the root flare is equal with the surrounding soil level. STEP 6

Make adjustments to the hole’s depth if necessary.STEP 7

Fill in your hole with the dug-up soil. Lightly compact the soil as you begin to reach ground level.STEP 8

Ensure the root flare is fully exposed to oxygen and not mounded with soil.STEP 9

Take a picture and tag @RussellTreeExperts on Instagram & Facebook! You are now finished planting your tree sapling!STEP 10

Learn more about the TREE FOR A TREE® program!5000 Trees Planted in One Day!

Last Friday all of our employees took the day off from their normal duties and came together to plant 5,000 trees at Pickerington Ponds Metro Park for our TREE FOR A TREE® program! The initial idea of this program was simple, plant a tree for every tree that we remove — Flash forward almost 3 years and we are very happy to see this program continue to grow as we have now planted over 12,000 trees at 16 different sites in central Ohio.

Leave Those Leaves!

Of all of our seasons, I’ve heard more people proclaim their love of fall than any of the others. It marks an end to the uncomfortable heat of summer and traditionally represents a time when we reap the gifts of the harvest and prepare for winter. And for several weeks, our trees also gift us with a wonderful display of color. Everyone has a favorite - the brilliant orange of our native sugar maples, the rich yellow of the non-native maidenhair tree (Ginkgo), the reds, purples, and browns of oaks.

Please note: This article was originally published on 10/16/2020 and was republished on 11/11/2021.

Of all of our seasons, I’ve heard more people proclaim their love of fall than any of the others. It marks an end to the uncomfortable heat of summer and traditionally represents a time when we reap the gifts of the harvest and prepare for winter. And for several weeks, our trees also gift us with a wonderful display of color. Everyone has a favorite - the brilliant orange of our native sugar maples, the rich yellow of the non-native maidenhair tree (Ginkgo), the reds, purples, and browns of oaks.

Fall is a time marked by traditions. And when those beautiful leaves begin to fall, we have another long-standing tradition. We clean them up, put them out at the curb, and praise ourselves for the hard work and tidy-looking yard. In doing so, we avoid being “that neighbor” who doesn’t clean up their leaves, which, with a few windy days, find their way back into everyone else’s yards. By cleaning them up, we also avoid a build-up of debris, moisture, insects, and pests in the outside corners of our homes, fences, yards, etc. There are plenty of reasons why we don’t want to just leave the leaves wherever they fall.

But in cleaning up all of those leaves, we are also inadvertently disrupting a natural process and contributing to a host of very common problems in our landscapes. As mentioned above, fall is the season of harvest. As it turns out, this holds true for our trees as well. Even though they have been manufacturing food for themselves throughout the year by way of photosynthesis, in the fall, the leaves that fall to the ground begin a slow process of decomposition. Eventually, if left in place, they will become organic matter that improves soil structure and provides a wealth of needed nutrition to the root systems of trees. I like to think of this as the tree’s gift of a fall harvest to itself.

One of the most widespread problems that this “clean up” contributes to is the chlorosis that we see in common landscape trees like red maples, pin oaks, and river birches. You don’t have to look very hard to find a red maple or pin oak in an undisturbed wooded area in central Ohio. But you’d be hard pressed to find one in such a natural environment that is struggling with chlorosis. This is because the soil in these areas contains more organic matter, and in turn contains more nutrients and also a lower pH level, which allows the key nutrients associated with chlorosis to be properly absorbed by the tree roots. When we look at it this way, chlorosis is a man-made problem, typically only found in our urban landscapes where we create conditions that aren’t always best for our trees. Some other issues that leaf cleanup can contribute to are general nutrient deficiencies and also surface roots, where roots must grow closer to the surface in an attempt to get more oxygen due to the dense clay-heavy soil that is lacking an adequate amount of organic matter.

So what’s the solution? How do we help provide suitable conditions for our trees without abandoning leaf cleanup and annoying the neighbors? There are a few things we can consider:

#1

Leaf mulching in the lawn

Though this may have limited benefit to a tree’s roots due to the aggressive nature of turf and its ability to successfully compete for water and nutrients, mowing over the leaves instead of raking them will help to return some leaf litter to the yard and possibly increase the amount of organic matter in the soil.

#2

Leave the leaves!

Wherever possible, try to leave the leaves that fall and let them break down over the winter months. Perennial beds located around trees are a great place for this, where you should be considering leaving the dead perennial tops until spring for the same reason. In many urban landscapes, there is unfortunately a limited number of areas in the yard where this is an option, since the expectation is to have neatly mulched beds and crisp bed edges. Whether that approach is right or wrong is largely a matter of opinion, but it definitely does not favor the overall health of our trees.

#3

Reduce the size of the lawn

We recommend that turfgrass is removed from within the drip line of the tree. The leaves that fall each year will then be able to stay within this area, decompose, and provide vital nutrients back to the tree.

In writing this article, I considered titling it “Tear Out That Turf!” instead of “Leave Those Leaves!”. Turf grass is an amazing groundcover that gives us outdoor spaces that we can enjoy in a number of ways. It’s so hardy, we can literally trim it once a week and drive vehicles over it without killing it. Try doing that with just about any other type of plant, and the results won’t be pretty. But along with being hardy, it requires a significant amount of resources. And perhaps more relevant to this article, we can’t leave it covered with leaves and expect it to survive. Trees and grass represent parts of our natural world that are typically separate from one another. Most of the world’s trees grow in communities that we call forests. Grasses are sun-loving plants naturally found in prairies, fields, and meadows where they don’t get buried in leaf litter once a year. Generally speaking, the one place in the world where they are found coexisting is in our yards, artificially so, and with a lot of help from us. One of the best things you can do for your trees is to increase the space around them and under them that is void of turfgrass. This will reduce the amount of competition for water and nutrients, and also allow for a larger area of soil that you can improve with leaf litter or other soil amendments. It’s important to exercise caution if you choose to remove the turf around your trees so as not to damage the roots that may be present immediately underneath. If you decide to go this route but want some help, we offer a service called root-zone invigoration, which uses high-pressured air to remove turf and cultivate the soil without any mechanical damage to the delicate root system. This is often done for a specific reason related to a tree’s health, but it is also one of the best ways to increase the turf-free zone around a tree.

IN CLOSING…

I’m confident that no lawn care company ever has or ever would write an article about leaving leaves and getting rid of turfgrass, but as an arborist, I'm probably biased towards the trees. Many of the tree-related issues that occur in our urban landscapes are a result of the conditions we create. Allowing for a more natural approach while stilling doing our part to maintain the property should be something we all consider. As always, give us a call or email us with any questions. Just not questions about your lawn, we’ll probably tell you to tear out that turf!

Walter Reins | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Walter has been an ISA Certified Arborist since 2003. He graduated from Montgomery College in Maryland with a degree in Landscape Horticulture, and has called Columbus, OH his home for nearly 20 years. Walter appreciates trees for their majesty and the critical role they play in our world.

What's Going on with My Oak? Part 2

Earlier this year, we shared an article that highlighted two issues that were tied to recent weather patterns and had many homeowners concerned about their oak trees - one was an insect (Oak Shothole Leafminer) and another was a fungal pathogen (Oak Anthracnose). Combined, they made for unsightly leaves that were riddled with holes and brown patches. Fortunately, both issues were more of an aesthetic concern than anything else, and neither of them required treatment or had any lasting effects on the overall health of the trees. In fact, they are both likely to occur each year to some degree and should not be reason for concern.

Earlier this year, we shared an article that highlighted two issues that were tied to recent weather patterns and had many homeowners concerned about their oak trees - one was an insect (Oak Shothole Leafminer) and another was a fungal pathogen (Oak Anthracnose). Combined, they made for unsightly leaves that were riddled with holes and brown patches. Fortunately, both issues were more of an aesthetic concern than anything else, and neither of them required treatment or had any lasting effects on the overall health of the trees. In fact, they are both likely to occur each year to some degree and should not be reason for concern.

As we move through one of the hotter Ohio summers in recent memory, some oaks are dealing with yet another issue that is blemishing their leaves and even causing significant early defoliation. This time the culprit is a different foliar fungal issue called Tubakia Leaf Spot (pronounced “tu-bock-ee-ah”). This disease is much like the issues that we saw earlier this year in that it’s not something we need to treat and should be thought of as mostly an aesthetic issue. However, unlike the issues we saw in the spring, this one may indicate some underlying concerns that can be addressed.

Additional examples of Tubakia Leaf Spot

Heat and Drought Stress

With the heat of summer comes potential heat and drought stress for trees. If an oak exhibits signs of significant spotting and leaf drop from Tubakia, being proactive the following year and providing supplemental irrigation may help to reduce the effects of the disease. It may also be worth considering deep root fertilization as a way to help the tree regain its vigor and better handle the disease the following season.

Chlorosis

Chlorosis in an oak tree in Bexley, Ohio

Another common issue that many oaks struggle with is chlorosis. Chlorosis is a yellowing of the tree’s leaves that is often associated with high soil pH levels and can result in micronutrient deficiencies that affect the tree’s overall health and ability to withstand secondary stressors like insects, drought, and fungal diseases. It is a slowly progressing issue that causes a tree to decline over decades, and therefore often goes unnoticed by homeowners who just assumed their oak was supposed to be a little “yellow” looking. We’ve shared previous articles that go into greater depth regarding chlorosis, but it’s mentioned here because if your oak is chlorotic, the defoliation that can occur from Tubakia will likely be much more pronounced. Combined with the heat of summer, many oaks that are chlorotic and have Tubakia can start to defoliate at an alarming rate by mid-August. If this describes your oak tree, consider it a message that your tree is asking for a little TLC. Addressing the issue of chlorosis will help improve the health of your oak and improve its ability to deal with other stressors.

It’s worth mentioning that the issues discussed here can produce symptoms that an untrained eye may misinterpret as Oak Wilt. Oak Wilt is a serious systemic fungal disease that can, and typically does, lead to the decline and death of otherwise healthy oaks once infected. If you’re concerned about your oak tree, take a few photos of the leaves and send them to us. We may be able to determine what’s happening and put your mind at ease. If we’re not sure, we’ll schedule a visit to further inspect the tree. Even for trained arborists, Oak Wilt can only be 100% confirmed through diagnostic testing in a lab. If we suspect Oak Wilt, we will recommend this testing be done right away. Be careful with online searches as an attempt to “self-diagnose”. This often leads us down a very incorrect path when we do it regarding our own health concerns, and it’s typically no more accurate when we apply it to other living things. Ask the experts, it’s what we’re here for.

Walter Reins | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Walter has been an ISA Certified Arborist since 2003. He graduated from Montgomery College in Maryland with a degree in Landscape Horticulture, and has called Columbus, OH his home for nearly 20 years. Walter appreciates trees for their majesty and the critical role they play in our world.

Best Practices for Watering Your Trees

Last Fall I planted a Nikko maple (Acer maximowiczianum) for one of my neighbors. Somewhat uncommon, Nikko maple is a small statured, 20 - 30’ at maturity, trifoliate, hardy tree with nice fall color. It has good urban tolerance and was a good fit for its location with overhead utilities. I have been watering this tree somewhat regularly with a large watering can that I can easily carry across the street and have been pleased with the healthy appearance and good amount of new growth that has emerged this year. As far as I could tell the tree looked great so you can imagine my surprise when I came home recently from a long weekend getaway and discovered that the top half of the tree’s canopy had turned brown.

Please note: This article was originally published on 8/13/2020 and was republished on 8/1/2023.

Last Fall I planted a Nikko maple (Acer maximowiczianum) for one of my neighbors. Somewhat uncommon, Nikko maple is a small statured, 20 - 30’ at maturity, trifoliate, hardy tree with nice fall color. It has good urban tolerance and was a good fit for its location with overhead utilities. I have been watering this tree somewhat regularly with a large watering can that I can easily carry across the street and have been pleased with the healthy appearance and good amount of new growth that has emerged this year. As far as I could tell the tree looked great so you can imagine my surprise when I came home recently from a long weekend getaway and discovered that the top half of the tree’s canopy had turned brown.

I approached the tree expecting to see an insect infestation, disease presence, or mechanical damage from my neighbor getting to close with his string trimmer. I could find none of these things. Upon closer inspection I noticed that the soil around the base of the tree was cracked, hard and dry and that I simply had allowed the root system to dry out. I felt like such a greenhorn. I immediately watered the tree with a slow deep soaking and will continue to do so through the end of October.

An arborist is not supposed to make this mistake but I share this story to show you how it can happen to anyone and to illustrate that there is a better way to water, and that watering is the single most important maintenance factor in the care of newly planted trees.

Many of the calls that come through our office are a result of improper tree watering, both directly and indirectly. Some are regarding trees that were planted and simply never watered, others are regarding trees that have experienced significant drought stress and now have been impacted by pest and/or disease problems targeting a vulnerable host.

Drought stress develops in trees when available soil water becomes limited. Newly planted trees are at the highest risk of drought stress because they do not have an extensive root system. As the soil dries it becomes harder and more compact reducing oxygen availability. When this happens young feeder roots can be killed outright further reducing the trees ability to absorb sufficient water even after it may return to the soil.

Why is water important to trees? Trees require water for two important functions: (1) Photosynthesis: the process by which plants synthesize food and (2) Transpiration: a process where water evaporates from the leaves and is drawn up from the roots helping to move nutrients up the tree.

No water in the soil means no nutrient transfer and no photosynthesis. This generally equates to tree death.

Knowing the best way to deliver water is the single most important maintenance factor in the care of newly planted trees so here are some basic guidelines and tips to follow to make sure you are getting the most out of your watering efforts:

When to water

Newly planted trees should be watered one to two times per week during the growing season. The best time to water is early in the morning or at night. This allows trees the opportunity to replenish their moisture during these hours when they are not as stressed by hot temperatures. Watering at night allows more effective use of water and less loss to evaporation. Side note: If watering at night, a system that directs water into the ground and away from the foliage is recommended. Some foliar fungal diseases like apple scab or needle cast can thrive on foliage that remains wet through the cool nighttime hours.

How to Water

The best way to water newly planted trees is slowly, deeply and for a long time so that roots have more time to absorb moisture from the soil. A deep soaking will encourage roots to grow deeper as opposed to frequent shallow watering which can lead to a shallow root system more vulnerable to drying out (like my Nikko maple).

I like to water trees slowly two different ways. Around my house I use a garden hose with the pressure turned low so that water is coming out at a slow trickle. I place the end of the hose on the root ball a few inches away from the main stem and leave it in place 30 - 60 minutes depending on the size of the tree. This should be done at least once a week during the growing season. Verify that water is coming out slowly and seeping into the soil rather than just running off into the lawn. For trees that are outside the range of my hose, I like to use 5-gallon buckets with two small holes poked in the bottom of one side. These can be filled up quickly with the hose but will drain slowly, ideal for a slow soaking. Two 5-gallon buckets once a week should suffice for most newly planted trees, depending on the size.

Where to water

It is important to understand that for the first growing season after planting, most newly planted tree's roots are still within the original root ball. This is where watering efforts should be focused. The root ball and the surrounding soil should be kept evenly moist to encourage healthy root growth. It can take two or more growing seasons for a tree to become established and for its roots to venture into the soil beyond the original root ball.

Trees under stress from disease or insect predation and trees in restricted root zones (trees surrounded by pavement) could take longer to establish.

Other important tips

Avoid fertilizing during drought conditions - synthetic fertilizers can cause root injury when soil moisture is low. Fertilizing in the summer could also cause additional new growth requiring additional moisture to support it.

A 1 - 2” layer of organic mulch over the root zone of the tree will help to conserve water.

The goal of watering is to keep roots moist but not wet. Excessively saturated conditions can also damage tree roots.

A “good rain” or even an irrigation system is not sufficient for most new tree plantings

During extended periods of drought all trees (including established ones) benefit from supplemental watering.

TJ Nagel & José Fernández posing for a photo for this article! Happy watering, everyone!

Remember, proper watering is the single most important maintenance factor in the care of newly planted trees. I am intentionally redundant on this point because it cannot be overstated. Air temperatures, precipitation, tree health, tree size, soil texture, etc. can all influence a tree's need for water. This article is intended to be a basis for proper tree watering procedures and cannot address every tree watering scenario. Happy watering and may your rain barrels always be full.

TJ Nagel | Scheduling Production Manager, Russell Tree Experts

ISA Certified Arborist® OH-6298A // Graduated from The Ohio State University in 2012, Earned B.S. in Agriculture with a major in Landscape Horticulture and minor in Entomology // Tree Risk Assessment Qualified (TRAQ) // Russell Tree Experts Arborist Since 2010

Time Passing By

I pause for a moment and take a photo of the weeping beech. Its leaves have just fully expanded and are hardening off. What is striking about it is the tender new growth at the branch tips. Almost rubbery in quality, like licorice, it grows in an unusual zig-zag pattern repeated throughout the whole tree. Unusual for other trees, but not for this one, so I think that I want to write an article about new growth emerging in trees, and how some trees grow much faster than others.

I pause for a moment and take a photo of the weeping beech. Its leaves have just fully expanded and are hardening off. What is striking about it is the tender new growth at the branch tips. Almost rubbery in quality, like licorice, it grows in an unusual zig-zag pattern repeated throughout the whole tree. Unusual for other trees, but not for this one, so I think that I want to write an article about new growth emerging in trees, and how some trees grow much faster than others.

There are other pictures I have taken as well that would work for such an article showing astonishing growth in a cottonwood (4 feet!), and similar growth in a sycamore (3 feet). Those photos are from March 14. The photo of the weeping beech is from May 15. I took some other photos of what I call the second wave of spring, showing the second flush of growth that some trees have after the initial burst in early spring that is usually followed by fruit production. Those photos are from June 25. “The second wave of spring”, I thought, would make a great title for another article.

Here we are on August 6 and neither of those made it out of my thoughts and onto my keyboard.

After the seeming sameness of winter, patterns start to flow; the landscape changes in texture and color almost constantly, like the earth is a giant kaleidoscope that changes the pattern with each turn. This isn’t readily noticed unless one is watching in the same general area, memory serving as a time lapse reel of images rising, blending, fading into something new. I have watched the raspberries bloom, set fruit, ripen, followed shortly after by the blackberries. Today they are in flower, tomorrow I am picking and sampling as I walk by. Earlier in June I have sampled the offering of different serviceberry trees, savoring very slight variations in flavor. These are plants that seem to go from flower to fruit almost overnight. Others play a longer game: pawpaw is one of the earliest bloomers in Ohio, the purplish, brownish flowers easily missed in early, early spring. Then the tiny fruits appear and begin to swell. By now they are the size of small mangos, and will grow even larger as they ripen. It’s hard to think the fruit will be ready for first tasting around the first or second week of September. That’s only a month away!

Through July I noticed ironweed flower buds starting to swell. “Those will be a nice purple in August”, I thought. Then last week I saw the first plant starting to bloom. Sure enough, it was July 31. Almost like that plant just could not wait for its turn to show off.

These markers of passing time give me a sense of peace. I’m not sure why, but I think it is the thought of a repeating pattern that reassures me. Patterns and cycles are attributes of Order, yet the order is not so strict that it stifles individual expression. Yes, ironweed flowers in August, but it may not be in the same spot each year, and some plants may just be so excited that they bloom a day early. Colors and textures rise and fall, moving around us quite predictably, yet with such variation from season to season.

Pattern. Cycles. Expression. Order.

Time will carry on. All is well. Soak in the sun, drink in the rain. Both are provided free of charge, and we have been given a moment in time and a body in space in order to enjoy it all. This is very good. Let’s not miss it.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

Summer Update

As we have wrapped up our first month of summer you may find yourself wondering, “What’s going on over there at Russell Tree Experts?” Well, let me fill you in!

As we have wrapped up our first month of summer you may find yourself wondering, “What’s going on over there at Russell Tree Experts?” Well, let me fill you in!

Storms

Our crew working hard to resolve storm damage at Valley Forge National Historical Park on June 11th, 2020

Let’s start with storms. This summer has provided quite a bit of severe weather. From trees on houses to branches littering the yard, we have seen it all. We had crews dispatched all over Columbus and we even mobilized to help mitigate storm damage in Valley Forge National Historical Park, PA. Our crews have been on high alert working late into the evenings helping to clean up central Ohio. It is only through their hard work and perseverance that we were able to help all those who reached out for our help and services. I would like to take a moment to thank all of our crew members for staying safe and toughing it out through all these weather events and remind you to always do a safety check of your property after any high winds.

Check out the above video of our crew removing a hazardous tree that uprooted and fell down in a client's yard in Columbus, Ohio during a windy thunderstorm.

Training

Joe Russell conducting traffic control training

Next let’s talk about training. In June, Russell Tree Experts (RTE) dedicated two weeks of individualized training for our team members. Each crew had the opportunity to spend time where dedicated trainers helped to advance their arboriculture expertise. It is always an exciting time to watch our employees’ passion as they try out new techniques or operate new gear and equipment for the first time. Some of the most important items we touched on were traffic control and aerial rescues. With traffic being an ever-present danger in our industry we have turned to technology wherever possible. We had hands on training with our automated flaggers allowing crew members to control traffic without being in harm’s way. Job site setup is critical in this industry and knowing precisely how to setup cannot be over stressed. Aerial rescues are also another very important part of training. We were able to setup real life situations and go over step by step instructions on how to handle any emergency situation. This type of training is invaluable in real life applications. However, our training did have some more exciting moments. We had new members climb for the first time, practice felling notches, and even climb a tree on spurs for the first time. The training was a great success and we look forward to our next event.

In Closing

Lastly, RTE has stayed busy over these last months and we have brought on a few new production employees. The character and drive of these members has me excited for their career here and ready to help them start their adventure into the canopy. While it is a slow process learning all of the necessary safety procedures and the processes for all that we do it is an exciting time. Nothing is more rewarding than watching someone progress through this industry and I am thankful to have the opportunity to be part of their future here are Russell Tree Experts.

From our little family here at Russell Tree Experts, I wish everyone the best out there and remember to stay safe.

Andy Bartram | Production Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Roots are Dry. Water your Trees!

Don’t let the extremely wet spring and recent rains fool you. It is already drying out more than you may think. With the recent hot temperatures and quick thunderstorms most of the water tends to run off. Most recommendations for watering trees and plants call for the equivalent of 1 inch of rain per week. I have already witnessed plant material struggling due to lack of moisture.

[click to enlarge]

Don’t let the extremely wet spring and recent rains fool you. It is already drying out more than you may think. With the recent hot temperatures and quick thunderstorms most of the water tends to run off. Most recommendations for watering trees and plants call for the equivalent of 1 inch of rain per week. I have already witnessed plant material struggling due to lack of moisture. The first thing I check on a struggling plant is the planting depth, the amount of mulch or soil on top of the root ball and the amount of moisture in the root zone. Proper planting and watering are the best defense for most problems we see in the landscape. Whenever possible, identify the root zone on your plant material and only apply 1 to 2 inches of mulch over the root zone. Thoroughly soak at least once a week.

If history repeats itself like last year, we had a pretty severe drought towards the end of the summer of 2019. We lost a lot of plant material due to the extremely dry conditions. One plant that we saw having a lot of problems last year during the drought was the Emerald Green Arborvitae, this variety seemed to have the most casualties during last year’s drought. Recently planted trees and shrubs are also very vulnerable during hot, dry periods.

Pictured here is a dead Emerald Green Arborvitae due to extremely dry conditions in the fall of 2019.

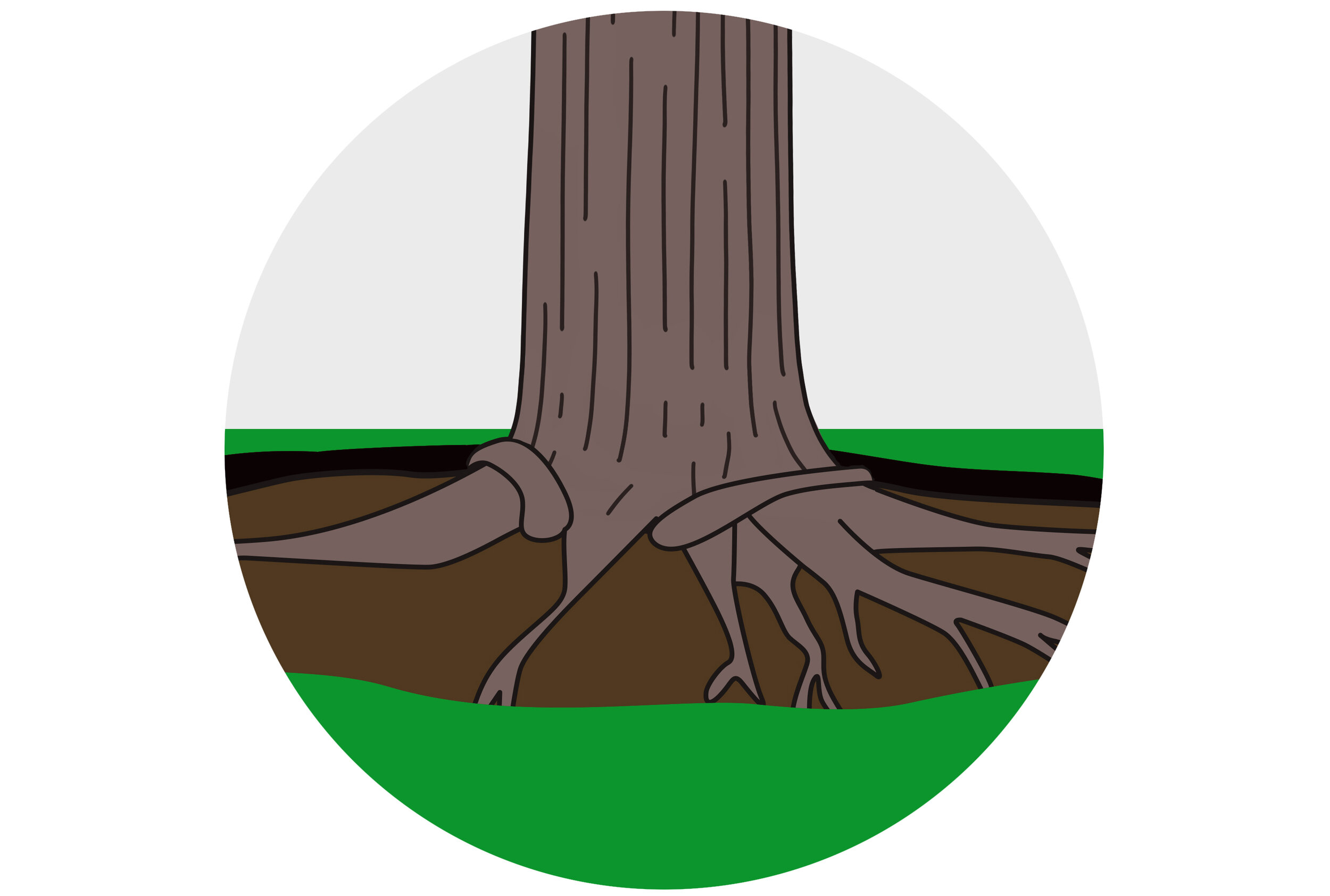

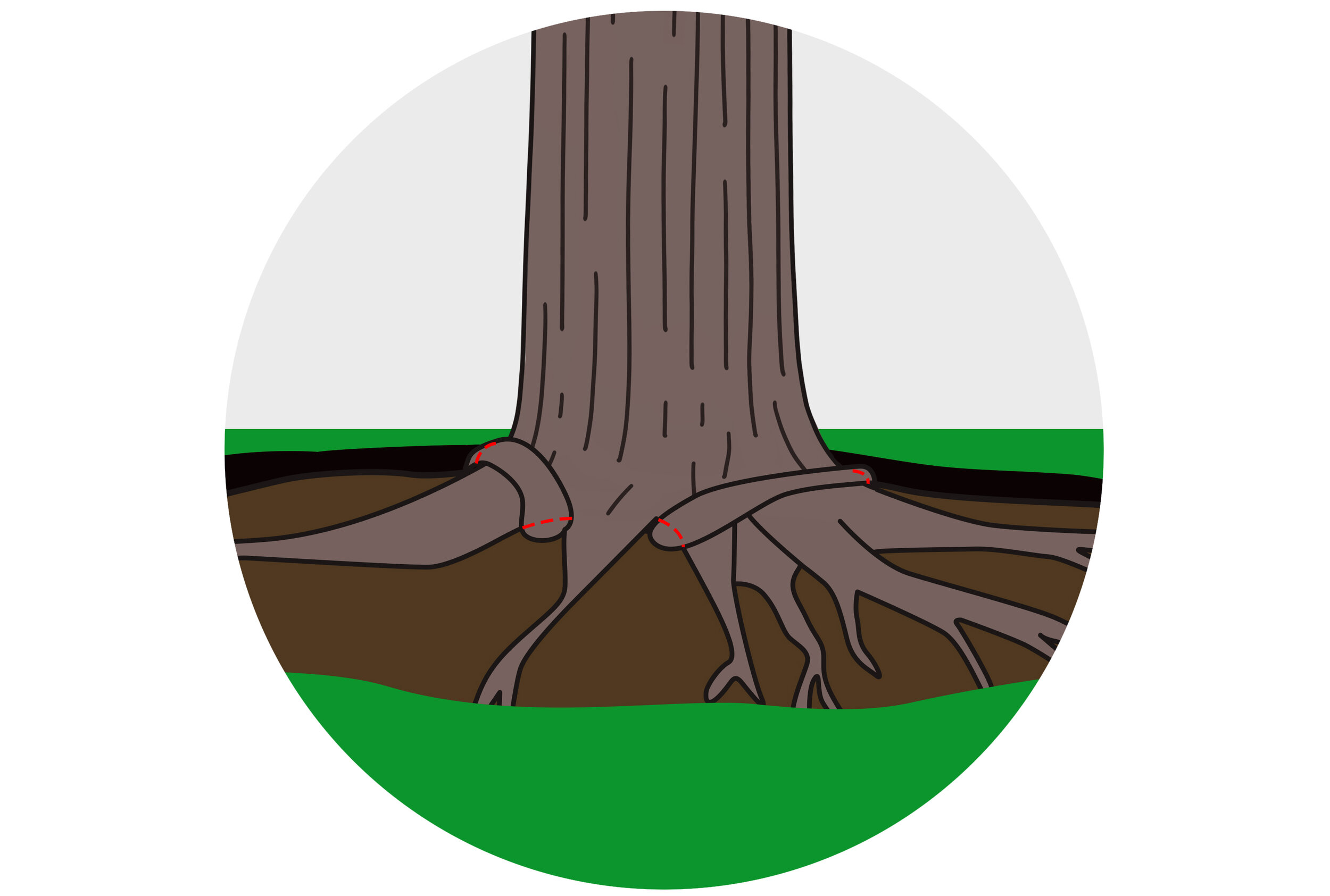

Another thing to check on struggling plant material would be to check for girdling roots which unfortunately has become a major problem in today’s landscape. On small plant material this can be accomplished with careful digging and washing soil away from the root system to check for roots that are circling the tree and possibly strangling itself. The most damaging of these roots should be removed to help improve the root structure moving forward. For larger trees this can be accomplished with an instrument called an Air Spade. This procedure is usually completed in the fall or early spring to remove damaging roots when it has the least amount of impact on the tree itself. The air spade quickly removes soil from the roots using air pressure making it easy to identify girdling roots. In extreme cases the offending roots may need to be removed in stages over a couple of years to avoid over stressing the plant.

In summary it is very important to remember that what you see above ground often mimics what is happening underground. Take the time to make sure your trees are planted properly and keep them watered.

Mike McKee | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Mike graduated from Hocking College in 1983 with a degree in Natural Resources specializing in urban tree care. He has been a certified arborist since 1991. Mike started his career in the private industry in 1985 before becoming a municipal arborist in1989. He retired after serving thirty years before joining us at Russell Tree Experts in Sept. of 2018. His love of trees has never waned since trying to climb up the ridges of the massive Cottonwood tree in front of his childhood home.

Worms by the Bagful

Worms by the bagful. Bagworms, that is. This interesting insect is not really what we would usually call a worm, but is considered a caterpillar instead. While most caterpillars pupate into a flying adult (moth or butterfly), the female of this species never emerges from her mobile home. The male does, and he flies to the female so they can engage in activities that ensure the species does not die out.

Bagworms, that is.

This interesting insect is not really what we would usually call a worm, but is considered a caterpillar instead. While most caterpillars pupate into a flying adult (moth or butterfly), the female of this species never emerges from her mobile home. The male does, and he flies to the female so they can engage in activities that ensure the species does not die out.

After mating, both male and female eventually die, leaving many eggs within the female bag. These eggs hatch the following spring to cause more foliar damage as they feed on many kinds of plants, sometimes causing irreversible damage and death if left unchecked.

I focus on this pest for this article because I have been watching for its emergence this season wondering when it would finally show up. Early June is usually when we start seeing the new generation of this pest (630 growing degree days, according to the OSU OARDC calendar available here). Last season I recall bagworms emerging later than usual, and I was curious what would happen this year given the very unusual spring we have had. Yesterday I spotted my first bagworms in a client’s back yard – the smallest I have ever seen yet. The plant had been damaged in the past season by bagworm feeding, and the old adult bags were clearly visible. When I looked closely, I could just make out the very tiny, brand new bagworms moving about as they fed on the plant.

Very tiny, brand new bagworms

They had also established on the neighboring, more healthy, plant.

I checked the current growing degree days, and we are at 959 today for the area I was in. I can’t say when these baby bagworms were hatched, but it has not been long. I also do not know if there is a period between the hatching of the eggs and the emergence of the caterpillars from the old cocoon. As with everything in nature, there is always variation from season to season, and from place to place within the same season, so scouting is always the best way to determine when pests are present or not.

Bagworms feed on a number of species, but evergreen species are the most at risk of permanent damage or death. If an evergreen is defoliated rapidly by large quantities of these mobile marauders, it will likely not have the ability to rapidly regenerate foliage to make up for that which was lost. I commonly drive past juniper, spruce, and arborvitae that have been sheared of green foliage by bagworms.

Thankfully, if caught early, this insect pest is relatively easy to control. Two treatments are sometimes recommended to make sure any late starters are caught during the second round. I routinely show clients what a bagworm looks like because they are very easy to miss within a plant. As they feed and grow they use foliage from the plant they are feeding on to build the bag that gives them their name. This means they look like part of the plant. Once identified though, they are easy to spot. If treatment is no longer an option (when the pest is settled for the winter or no longer actively feeding), removal of the bags by hand is a very good way to control this pest. This method works best on smaller plants since it is essential that every single bagworm is removed from the plant.

Thank you all for taking the time to read this article. If it is shorter and less philosophical than usual, it is because we are striving to keep up with the all the requests for service that keep coming in. I look forward to being able to take a slow breath later in the season and make some time for reflection. In the meantime, thank you very much for trusting us with your trees.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

[Quick fact checks from https://bygl.osu.edu/node/1048 and https://www.mortonarb.org/trees-plants/tree-and-plant-advice/help-pests/bagworms.]

What’s Wrong with My Oak?

Each year around this time, as yards come alive at an unstoppable pace, we receive calls from customers and concerned tree owners all around town with questions about trees. As arborists receiving all of those calls, we’re fortunate to see patterns that help us quickly determine if an issue is an isolated occurrence or if it’s happening on numerous trees. When we receive multiple calls that describe the same concerns, we immediately consider weather patterns and how they may play into it.

Each year around this time, as yards come alive at an unstoppable pace, we receive calls from customers and concerned tree owners all around town with questions about trees. As arborists receiving all of those calls, we’re fortunate to see patterns that help us quickly determine if an issue is an isolated occurrence or if it’s happening on numerous trees. When we receive multiple calls that describe the same concerns, we immediately consider weather patterns and how they may play into it.

This year we had a very cool and wet start to our spring, not unlike last year. One of those patterns we’ve received numerous calls about is the brown blotches and holes that many homeowners are seeing on their oaks. One half of this relates to the spring weather, the other may simply be more noticeable because of the increased overall unsightly appearance of the leaves.

There are likely two culprits at work here, an insect and a fungal pathogen. The holes you may be seeing in your oak leaves are caused by the Oak Shothole Leafminer. This feeding activity happens as the leaves are still in the bud or as they’re unfurling. Depending on when it occurs, it can even create symmetrical patterns on the right and left sides of the leaf. If we see these strange patterns, we naturally suspect one of two things: aliens, or those darn kids down the street. Alas, it’s just an insect. And a harmless one at that. The holes, while they may look alarming, will not affect the long-term health of the tree and no treatment is needed.

The brown and diseased looking portions of the leaves, usually at the tips or edges, is Oak Anthracnose. This fungal disease is active during the cooler and wet weeks of spring. By the time we see the damage to the leaves, there isn’t anything that can be done. Fortunately, just like with the insect mentioned above, there really isn’t anything that needs to be done. Leaves that are affected significantly enough may fall off prematurely, but most will persist in the tree throughout the season. While the name of this disease sounds alarming, it’s overall effect on the health of an oak is typically a non-issue.

There’s a fabulous online article that covers both of these issues and can be found on the Buckeye Yard and Garden Online website. It goes into much greater detail if you’re itching to understand the science behind what’s at work on your oak tree. Follow the link below for more information: https://bygl.osu.edu/node/1296

The Ohio State University Extension does a fabulous job with updating and maintaining this site. It is a wonderful resource for homeowners and industry professionals alike. I encourage you to explore its wealth of information and see what else you can learn about the trees in your yard and beyond.

Walter Reins | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Walter has been an ISA Certified Arborist since 2003. He graduated from Montgomery College in Maryland with a degree in Landscape Horticulture, and has called Columbus, OH his home for nearly 20 years. Walter appreciates trees for their majesty and the critical role they play in our world.

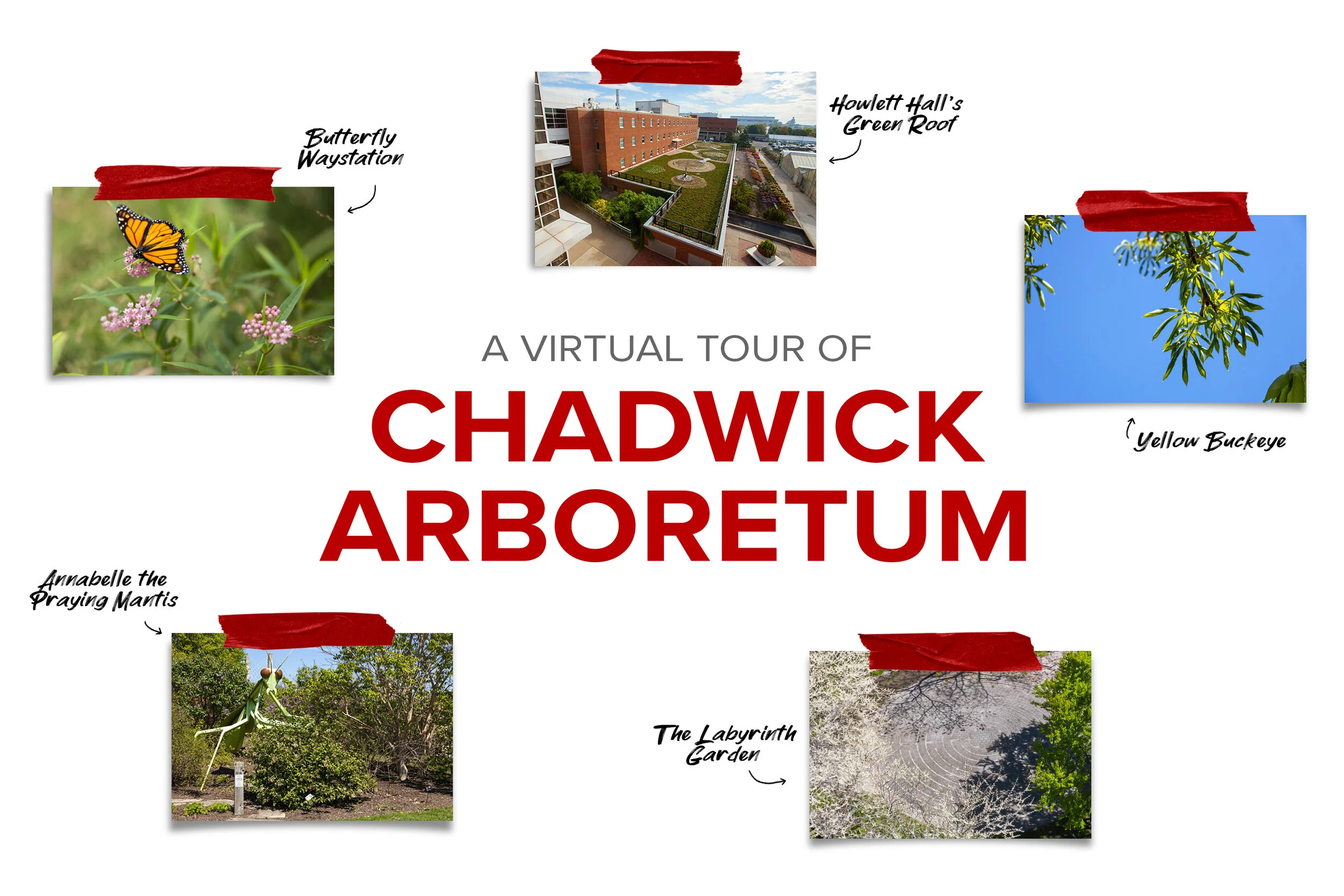

A Virtual Tour: Chadwick Arboretum

By Enrique Arayata

ISA Certified Arborist® OH-7252A

May 6, 2020

As a current student at The Ohio State University who was enrolled in HCS 2200: The World of Plants last Spring 2020 semester, I was disappointed to hear that the tour to Chadwick Arboretum and Learning Gardens was canceled, understandably so, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In its place, my professor assigned a virtual tour of the area. Today, I would like to share some of the interesting aspects of Chadwick Arboretum and Learning Gardens to encourage you to go on a socially distanced walk to explore the area and take your mind off of everything currently going on in the world. We will be visiting Howlett Hall and its green roof, the Phenology Research Garden, the Lois B. Small and Gladys B. Hamilton Labyrinth Garden, the Monarch Butterfly Waystation, and the Andy Geiger Buckeye Collection at Buckeye Grove.

“Gather around! The tour is starting!”

Howlett Hall’s green roof

Within Chadwick Arboretum and Learning Gardens is the green roof housed on top of Howlett Hall, a retrofitted roof containing living, breathing vegetation over a bed of sedum spanning across 12,000 square feet. The benefits of this green roof, apart from taking advantage of what would otherwise be a vacant and empty roof, is that it will prevent over 200,000 gallons of polluted water from entering the Olentangy River and will save over $10,000 annually through reduced energy costs and roof maintenance. (1) The green roof adds insulation to Howlett Hall, thus reducing summer air conditioning costs, and with the collected rainwater, it will also reduce, delay, and filter stormwater runoff. Overall, this green roof increases green space, biodiversity, urban food production, and food security, all while efficiently using urban space that will actually lengthen the lifespan of the roof.

“Let’s visit our next location!”

Annabelle the Praying Mantis at Phenology Research Garden