Is my boxwood trying to tell me something?

A truly fascinating and audible phenomenon is happening in Ohio gardens right now. The tiny worm-like larvae of the boxwood leaf miner have awoken and are voraciously feeding inside boxwood leaves.

A truly fascinating and audible phenomenon is happening in Ohio gardens right now. The tiny worm-like larvae of the boxwood leaf miner have awoken and are voraciously feeding inside boxwood leaves. This chewing can be so noisy that it can be heard standing several feet away, as I experienced while inspecting a property in Lewis Center last week. Typically, though, a crackling noise can be heard by putting your ear near an “unhealthy-looking” boxwood this time of year. If you gently break open a leaf, you will discover the hungry invaders, wiggling between the leaf surfaces.

Hear the sound of larvae feeding on the leaves of a boxwood — just Ignore the sound of the chirping birds!

These larvae will soon, within weeks, finish their development and exit the leaves as adult flies. They resemble small yellow or orange mosquitoes that hover around the shrub while they breed and lay eggs inside the new boxwood spring leaves. The eggs hatch in summer and begin to devour the internal leaf tissue causing blister-like wounds. A boxwood that has been infested for a few years will look sickly in general with yellow, orange, or brown splotches on the leaves. Defoliation and even death is possible if the infestation is extensive and left untreated.

Gently break open a leaf to witness the hungry invaders

If you notice a ruckus coming from your shrubs this spring, do not ignore it. Eavesdrop on them yourself or call Russell Tree Experts to have one of our knowledgeable arborists diagnose this pest and evict them from your shrubbery.

I wish you a lovely spring filled with the sounds of songbirds, not munching maggots.

Krista Harris | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Krista grew up in the central Ohio area and became an ISA certified arborist in 2017. She graduated from The Ohio State University with a Bachelor of Science in Crop Science and a minor in Plant Pathology in 2000 and has been in the green industry ever since. Her favorite trees are the American sycamore, American beech, and giant sequoia.

Lecanium Scale (Part Two)

Recently one of my clients in Dublin ended up with three crabapple trees that had a heavy infestation of lecanium scale. We tried some treatments but the trees had declined and the client made the wise decision to remove and replace them.

[Note: For an introduction to this insect pest and as background for this article, please read Part One here, if you have not already done so.]

What I Found, and What I Predict

I started working with Russell Tree Experts in April of 2012. Soon after that my colleagues and I became aware of a major epidemic of lecanium scale in communities on the east side of Columbus. Entire streets had trees that were covered in scale, noticeable to the eyes of discerning arborists because of how black the trees looked as we drove by. We watched in chagrin as the epidemic worked its way west. As the scale populations increased in my areas (central and western communities), I could no longer jokingly rib my colleagues about how they were not taking care of the trees in their areas. We were doing what we could, but many of the infested trees were larger ornamental pear, crabapple, and cherry trees that are not the best candidates for cover sprays. Recently one of my clients in Dublin ended up with three crabapple trees that had a heavy infestation of lecanium scale. We tried some treatments but the trees had declined and the client made the wise decision to remove and replace them.

Last year during a regular fertilization visit to this property, Andy, one of our Tree Wellness arborists, made a note that another tree had scale, this time in the back yard. I stopped out soon after to take a look. Here is what I found:

Second-instar nymphs that overwintered on the tree stems. Note white waxy covering beginning to form. Scales are in their final fixed position, actively feeding and growing. Note droplets of honeydew here and there.

Each of these nymphs will mature into adult females that will be about 10 times their current size by the time they lay their clutch of 100 or more eggs.

This is a new infestation. An old infestation would also have the dead female bodies of last year’s adults alongside the current generation. They would be dark brown and about the size of BBs used for air gun ammunition.

I made some notes for treatment recommendations and discussed options with the client. He decided not to pursue treatment. This was on April 23rd.

Nearly 6 weeks later in early June, I went back to this property for a different reason. While I was here I inspected the small crabapple. Much to my surprise, the second-instar nymphs had not grown. By this time they should have been at or near adult size, and they would be soft and slimy when crushed. I brushed some of the scales with my fingers and they rubbed off the tree stem like gray ash. They were dead. I checked the tree all over – no adults, all scales were dead. This tree had been treated with something very effective. You will recall from the first article that the insect stage most vulnerable to treatment is the first-instar nymph stage, which hatches from eggs laid by the adults that these second-instar nymphs would have become.

I knocked on the door.

During the ensuing conversation I found out that indeed, the tree had been sprayed with an unknown solution recommended somewhere on the internet. I encouraged my client, feeling very proud that they had taken matters into their own hands. “You killed every single scale!” I told him.

I shared the story with TJ back at the office and asked TJ to ask the client for the recipe when he talked to him to confirm our next visit to the property.

A week or two later, another client appeared on my calendar. Her problem was dieback on a crabapple, and Oakland nursery had recommended that she call us. As I walked around the front corner of the house I noticed lecanium scale on a shrub in the front bed. “Hmmm…” I thought. So I was not surprised when I saw the crabapple, a nice one, also had a heavy infestation of lecanium scale. There were the adults as expected.

Then I looked more closely. By this time of year there should have only been dying and dead adults on the tree, with possibly some first-instar nymphs feeding on the leaves. But here were dead adults alongside second-instar nymphs on the twigs. Not a single first-instar nymph to be found under a single leaf. I rubbed my finger across a few of the nymphs… Sure enough, they rubbed off easily, like ash.

Now my thoughts went back to the first client who had sprayed his tree with a home-cooked remedy. I carefully interviewed the current client and she was positive that no treatment of any kind had been made on her tree. I started to wonder.

This became a trend for the next few weeks, such that when I encountered lecanium scale several more times I was no longer surprised to see the same thing. This made me realize that the problem for the scale, and the blessing for the infested trees, had to be environmental.

Late winter of 2020 we had a two-week period of what I called “false spring”, when temperatures were far too warm for the season and I silently directed my thoughts to my trees, asking them not to believe that winter was over. Of course they ignored me and began to leaf out and flower. Then winter raged back in and the new growth was burnt, flower buds died, and spring looked less vibrant when it actually came on its normal schedule weeks later.

After that false spring, we had no less than 4 nights during two separate weeks when temperatures dropped well below freezing. I disguised my Japanese maples as ghosts using bedsheets to protect them from freezing after they had budded out. It was to no avail - all the new growth got burnt off. The same thing happened to many of you as well, since the cold snaps were widespread.

I propose the hypothesis that the second-instar nymphs of lecanium scale also believed in the false spring, and emerged along with their host plants. When the temperatures plunged below freezing four times during a prolonged cold spring all those nymphs were killed. Just like that, entire populations of this scale were dead. How many of you recall that we had snow on Mother’s Day last year? Well, if my hypothesis is correct, I present you with a blessing disguised as a late snow: For many of my clients the problem of a large population of a serious insect pest had been solved without applying a single drop of insecticide. That greatly helped me bear the disappointment of my disfigured Japanese maples!

Based on this hypothesis I close this article by making the prediction that this 2021 season my colleagues and I will continue to confirm a crash in the general population of lecanium scale. Those large trees that were not good candidates for topical sprays? No need to spray them after all. Though lecanium scales have their place within their ecosystem, when their population reaches damaging levels it is gratifying to see widespread control that has taken place with no human intervention. My only hope is that beneficial insects did not suffer in the same way.

As I close I have mixed feelings about how plants and insects are very much at the mercy of the environment. But I hope I have achieved my goal in sharing all this with you. By writing this I hoped you could see a little of what it is like when arborists try to decipher the clues they find from client to client, from tree to tree, from insect to insect. And I am still relieved to know that the lecanium epidemic may very well have been stopped in its tracks, at least for a time.

May you all be well, and may this coming season be full of “long days and pleasant nights.”

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

Best Practices for Watering Your Trees

Last Fall I planted a Nikko maple (Acer maximowiczianum) for one of my neighbors. Somewhat uncommon, Nikko maple is a small statured, 20 - 30’ at maturity, trifoliate, hardy tree with nice fall color. It has good urban tolerance and was a good fit for its location with overhead utilities. I have been watering this tree somewhat regularly with a large watering can that I can easily carry across the street and have been pleased with the healthy appearance and good amount of new growth that has emerged this year. As far as I could tell the tree looked great so you can imagine my surprise when I came home recently from a long weekend getaway and discovered that the top half of the tree’s canopy had turned brown.

Please note: This article was originally published on 8/13/2020 and was republished on 8/1/2023.

Last Fall I planted a Nikko maple (Acer maximowiczianum) for one of my neighbors. Somewhat uncommon, Nikko maple is a small statured, 20 - 30’ at maturity, trifoliate, hardy tree with nice fall color. It has good urban tolerance and was a good fit for its location with overhead utilities. I have been watering this tree somewhat regularly with a large watering can that I can easily carry across the street and have been pleased with the healthy appearance and good amount of new growth that has emerged this year. As far as I could tell the tree looked great so you can imagine my surprise when I came home recently from a long weekend getaway and discovered that the top half of the tree’s canopy had turned brown.

I approached the tree expecting to see an insect infestation, disease presence, or mechanical damage from my neighbor getting to close with his string trimmer. I could find none of these things. Upon closer inspection I noticed that the soil around the base of the tree was cracked, hard and dry and that I simply had allowed the root system to dry out. I felt like such a greenhorn. I immediately watered the tree with a slow deep soaking and will continue to do so through the end of October.

An arborist is not supposed to make this mistake but I share this story to show you how it can happen to anyone and to illustrate that there is a better way to water, and that watering is the single most important maintenance factor in the care of newly planted trees.

Many of the calls that come through our office are a result of improper tree watering, both directly and indirectly. Some are regarding trees that were planted and simply never watered, others are regarding trees that have experienced significant drought stress and now have been impacted by pest and/or disease problems targeting a vulnerable host.

Drought stress develops in trees when available soil water becomes limited. Newly planted trees are at the highest risk of drought stress because they do not have an extensive root system. As the soil dries it becomes harder and more compact reducing oxygen availability. When this happens young feeder roots can be killed outright further reducing the trees ability to absorb sufficient water even after it may return to the soil.

Why is water important to trees? Trees require water for two important functions: (1) Photosynthesis: the process by which plants synthesize food and (2) Transpiration: a process where water evaporates from the leaves and is drawn up from the roots helping to move nutrients up the tree.

No water in the soil means no nutrient transfer and no photosynthesis. This generally equates to tree death.

Knowing the best way to deliver water is the single most important maintenance factor in the care of newly planted trees so here are some basic guidelines and tips to follow to make sure you are getting the most out of your watering efforts:

When to water

Newly planted trees should be watered one to two times per week during the growing season. The best time to water is early in the morning or at night. This allows trees the opportunity to replenish their moisture during these hours when they are not as stressed by hot temperatures. Watering at night allows more effective use of water and less loss to evaporation. Side note: If watering at night, a system that directs water into the ground and away from the foliage is recommended. Some foliar fungal diseases like apple scab or needle cast can thrive on foliage that remains wet through the cool nighttime hours.

How to Water

The best way to water newly planted trees is slowly, deeply and for a long time so that roots have more time to absorb moisture from the soil. A deep soaking will encourage roots to grow deeper as opposed to frequent shallow watering which can lead to a shallow root system more vulnerable to drying out (like my Nikko maple).

I like to water trees slowly two different ways. Around my house I use a garden hose with the pressure turned low so that water is coming out at a slow trickle. I place the end of the hose on the root ball a few inches away from the main stem and leave it in place 30 - 60 minutes depending on the size of the tree. This should be done at least once a week during the growing season. Verify that water is coming out slowly and seeping into the soil rather than just running off into the lawn. For trees that are outside the range of my hose, I like to use 5-gallon buckets with two small holes poked in the bottom of one side. These can be filled up quickly with the hose but will drain slowly, ideal for a slow soaking. Two 5-gallon buckets once a week should suffice for most newly planted trees, depending on the size.

Where to water

It is important to understand that for the first growing season after planting, most newly planted tree's roots are still within the original root ball. This is where watering efforts should be focused. The root ball and the surrounding soil should be kept evenly moist to encourage healthy root growth. It can take two or more growing seasons for a tree to become established and for its roots to venture into the soil beyond the original root ball.

Trees under stress from disease or insect predation and trees in restricted root zones (trees surrounded by pavement) could take longer to establish.

Other important tips

Avoid fertilizing during drought conditions - synthetic fertilizers can cause root injury when soil moisture is low. Fertilizing in the summer could also cause additional new growth requiring additional moisture to support it.

A 1 - 2” layer of organic mulch over the root zone of the tree will help to conserve water.

The goal of watering is to keep roots moist but not wet. Excessively saturated conditions can also damage tree roots.

A “good rain” or even an irrigation system is not sufficient for most new tree plantings

During extended periods of drought all trees (including established ones) benefit from supplemental watering.

TJ Nagel & José Fernández posing for a photo for this article! Happy watering, everyone!

Remember, proper watering is the single most important maintenance factor in the care of newly planted trees. I am intentionally redundant on this point because it cannot be overstated. Air temperatures, precipitation, tree health, tree size, soil texture, etc. can all influence a tree's need for water. This article is intended to be a basis for proper tree watering procedures and cannot address every tree watering scenario. Happy watering and may your rain barrels always be full.

TJ Nagel | Scheduling Production Manager, Russell Tree Experts

ISA Certified Arborist® OH-6298A // Graduated from The Ohio State University in 2012, Earned B.S. in Agriculture with a major in Landscape Horticulture and minor in Entomology // Tree Risk Assessment Qualified (TRAQ) // Russell Tree Experts Arborist Since 2010

Worms by the Bagful

Worms by the bagful. Bagworms, that is. This interesting insect is not really what we would usually call a worm, but is considered a caterpillar instead. While most caterpillars pupate into a flying adult (moth or butterfly), the female of this species never emerges from her mobile home. The male does, and he flies to the female so they can engage in activities that ensure the species does not die out.

Bagworms, that is.

This interesting insect is not really what we would usually call a worm, but is considered a caterpillar instead. While most caterpillars pupate into a flying adult (moth or butterfly), the female of this species never emerges from her mobile home. The male does, and he flies to the female so they can engage in activities that ensure the species does not die out.

After mating, both male and female eventually die, leaving many eggs within the female bag. These eggs hatch the following spring to cause more foliar damage as they feed on many kinds of plants, sometimes causing irreversible damage and death if left unchecked.

I focus on this pest for this article because I have been watching for its emergence this season wondering when it would finally show up. Early June is usually when we start seeing the new generation of this pest (630 growing degree days, according to the OSU OARDC calendar available here). Last season I recall bagworms emerging later than usual, and I was curious what would happen this year given the very unusual spring we have had. Yesterday I spotted my first bagworms in a client’s back yard – the smallest I have ever seen yet. The plant had been damaged in the past season by bagworm feeding, and the old adult bags were clearly visible. When I looked closely, I could just make out the very tiny, brand new bagworms moving about as they fed on the plant.

Very tiny, brand new bagworms

They had also established on the neighboring, more healthy, plant.

I checked the current growing degree days, and we are at 959 today for the area I was in. I can’t say when these baby bagworms were hatched, but it has not been long. I also do not know if there is a period between the hatching of the eggs and the emergence of the caterpillars from the old cocoon. As with everything in nature, there is always variation from season to season, and from place to place within the same season, so scouting is always the best way to determine when pests are present or not.

Bagworms feed on a number of species, but evergreen species are the most at risk of permanent damage or death. If an evergreen is defoliated rapidly by large quantities of these mobile marauders, it will likely not have the ability to rapidly regenerate foliage to make up for that which was lost. I commonly drive past juniper, spruce, and arborvitae that have been sheared of green foliage by bagworms.

Thankfully, if caught early, this insect pest is relatively easy to control. Two treatments are sometimes recommended to make sure any late starters are caught during the second round. I routinely show clients what a bagworm looks like because they are very easy to miss within a plant. As they feed and grow they use foliage from the plant they are feeding on to build the bag that gives them their name. This means they look like part of the plant. Once identified though, they are easy to spot. If treatment is no longer an option (when the pest is settled for the winter or no longer actively feeding), removal of the bags by hand is a very good way to control this pest. This method works best on smaller plants since it is essential that every single bagworm is removed from the plant.

Thank you all for taking the time to read this article. If it is shorter and less philosophical than usual, it is because we are striving to keep up with the all the requests for service that keep coming in. I look forward to being able to take a slow breath later in the season and make some time for reflection. In the meantime, thank you very much for trusting us with your trees.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

[Quick fact checks from https://bygl.osu.edu/node/1048 and https://www.mortonarb.org/trees-plants/tree-and-plant-advice/help-pests/bagworms.]

A Word of Caution

Earlier this year I attended a talk on plant disease diagnostics as part of my continuing education as an ISA Certified Arborist. The talk was given by a highly respected individual whom I have had the pleasure of learning from since my early days as an arborist in central Ohio. This time, one of the first statements spoken caught my attention immediately. I paraphrase it into something like this:

Earlier this year I attended a talk on plant disease diagnostics as part of my continuing education as an ISA Certified Arborist. The talk was given by a highly respected individual whom I have had the pleasure of learning from since my early days as an arborist in central Ohio. This time, one of the first statements spoken caught my attention immediately. I paraphrase it into something like this:

When it comes to health, humans have spent most of their time and effort studying diseases of one single organism – humans. And when we go to a doctor and he or she does not have an immediate answer for what might ail us, we don’t shake our head in wonder and ask “Why? Why don’t you know what is wrong with me?” The doctor may prescribe certain tests to start to gather information on what is wrong with us, and we consider that to be a normal process.

In contrast, arborists and horticulturalists are faced with hundreds of species of plants, each with their own specific array of pests and diseases, and when faced with a problem we can’t immediately identify, saying “I don’t know” may not be considered an acceptable answer by the person whose plant we have been called to save.

This is a difficult subject for me to write about, but maybe sharing a bit of what goes through my mind when trying to figure out what went wrong with a sick or dead plant will help you as a plant owner see how things sometimes go, from an arborist’s perspective.

When I walk up to a plant that is declining, dying, or dead several things go through my mind. They are all based on the scientific concept of the disease triangle (Kenny put together a great summary here), but here are the steps I am following in my mind:

What is the species of plant? Does it look normal for its type?

What are the common issues this plant typically faces? Do the symptoms I am seeing match any of these issues?

What is the immediate environment of the plant? Is it what this type of plant needs to thrive?

Are there signs of pest predation? If no, is the problem root related? If yes, why are the pests here?

My thoughts will go back and forth among these general areas because so much is interconnected. For example, I may see borer activity near the base of the plant, but is that really the causal issue? Perhaps the plant is waterlogged, and has begun to produce alcohol because of that. The alcohol has attracted boring beetles. In this case treating the plant for borers will not make a difference to plant health – they are secondary to the fact that the plant is stressed by environmental conditions.

My main goal as an arborist is to give tree managers (current landscape owners) the best information I can so they can make the best decisions for their situation. For example, some pests and diseases can be treated with high success rates, others not so much. Some treatments, such as fungicide applications, are mostly preventive, and need to be applied frequently through each season for the best chance at being effective. All of this is communicated to the tree manager so the best decision can be made.

There is one thing I can assure each of you of, with confidence: If I know what is wrong with your tree, I will try to walk you through whether treatment is a good option or not. I may say, “X is a known prescribed treatment for this problem. Experience has shown me that sometimes trees respond well to this, and sometimes they do not. Here is the cost of X – it may or may not be the best approach for you or your tree”. You weigh your options and decide what makes the best sense to you. The tree may be an essential part of your landscape, or have great emotional value, meriting a “let’s do everything we can to save it” approach. On the other hand, it may be a tree you really don’t mind phasing out of your landscape, to make room for a tree that is better suited to that particular environment.

Things can get tricky though…

What about fertilization? Well, in most urban landscapes soil quality has proven to be very substandard compared to what trees and shrubs need to thrive. So we commonly recommend a general fertilization to help maintain good health for trees and shrubs. The product we use in particular is very good for this purpose: a low nitrogen formulation blended with organic products that help condition the soil as well as provide nutrients. (Why this is a good formula for trees is a topic that really needs to be discussed, but far larger than space in this installment will allow). Before I get to my word of caution, let me ask two questions:

We know that having good nutrition as people is essential for good health. But will eating the right foods guarantee good health for the rest of your life?

We take our pets to the veterinarian for their regular shots and checkups. Does this guarantee that our pets will never fall ill?

Both scenarios are true for trees, but sometimes I face tough questions from clients whose trees I have been caring for. “You fertilized my trees and shrubs, and now my shrubs are dead.” “I was told by another arborist that my oak had an iron deficiency, and you said to give it manganese instead. It has still not improved.”

I understand where questions like these come from, and I do not want to take them lightly. But I suppose my goal is for people to understand something crucial: I will prescribe what I believe to be the best approach for the health of a given plant, but trees and shrubs can still die. Sometimes I don’t know why. When that happens, there are only a few reasons that hold true:

I prescribed an incorrect treatment. If I did so knowingly, I am a charlatan, and not to be trusted. If unknowingly, perhaps I need more training, or it was a simple mistake.

I prescribed the right treatment, but conditions were such that the tree was too far in decline to begin with.

Something else besides what was being treated for caused the tree to die.

For the first reason, reputation serves to keep me in the clear. Reputation is based on how many people have experienced my service over time. As for learning, hopefully that never stops.

For the second reason, this happens more than I would like, but is only reasonable since by the time a tree is noticeably sick it has usually suffered for several years already. When I recognize this in a tree I try to steer people away from treatments that may not be successful even though they are the proper treatments to prescribe.

The third reason happens quite often as well, especially when environmental conditions change from one season to another.

So where does that leave us? The meaning of a treatment being prescribed and applied by an arborist of good reputation is that he or she believes it is the best next step needed to address a problem. Conversation and questions are always welcome, but we all know that sometimes the answers are not easy. Sometimes the answer requires humility and truth, and it may simply be “I don’t know. Let’s figure out what the next step is.” I have been with Russell Tree Experts for 8 years now, and there have been some difficult moments. But I am happy to say those are in the minority by far! There are many trees I can think of that have responded well to treatment, and are still alive because of it. And there are many tree owners who have lost their trees after attempting treatment who are still able to trust that we did what we could and for whatever reason it just did not work. Both of these scenarios are triumphs in my mind, because both scenarios represent the same good faith effort undertaken by arborist and tree manager working together.

Thank you for taking the time to read this lengthy article. I hope to visit with you in your landscape soon! I would also like to thank Shari Russell, TJ Nagel, and Annette Durbin for taking the time to read and comment on the first draft of this article.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

When and How to Prune Lilacs

Common lilacs (Syringa vulgaris) are a favorite landscape shrub here in Ohio and beyond, with flowers that provide beauty and an unmistakable fragrance every spring. Other cultivars of lilacs offer different habits and uses in the landscape, but provide the same display of flowers that we all love. In order to ensure you get the most flowers on your lilac year after year, it’s important to know when and how to prune them.

By Walter Reins

ISA Certified Arborist® OH-5113A

March 6, 2025

Common lilacs (Syringa vulgaris) are a favorite landscape shrub here in Ohio and beyond, with flowers that provide beauty and an unmistakable fragrance every spring. Other cultivars of lilacs offer different habits and uses in the landscape, but provide the same display of flowers that we all love. In order to ensure you get the most flowers on your lilac year after year, it’s important to know when and how to prune them.

When To Prune

As a general rule for all lilacs, they should be pruned immediately after they’re done flowering in the spring. Since lilacs set next year’s flower buds right after the current year’s flowers have faded, pruning later in the summer or fall will result in cutting off many or all of next year’s flowers. This rule of timing applies to the larger common lilacs as well as the cultivars that are shorter or more “shrub” like. While the “when” of pruning lilacs is fairly straightforward, the “how” gets a little trickier. To keep things simple for now, we’ll think of lilac pruning as either maintenance pruning or rejuvenation pruning.

How To: Maintenance Pruning

For any lilac shrubs that have not outgrown their space or are still producing vibrant flowers each year, regular pruning can simply consist of any shaping that you choose to do along with removal of dead, diseased, or broken stems. You can also remove spent flowers from your lilacs to help encourage a cleaner growth habit and appearance. It’s always better to do this type of pruning by hand, rather than shearing. When making cuts, try to cut back to an outward facing bud. A good pair of hand pruners is the perfect tool for this and makes for much better pruning cuts than hedge shears.

How To: Rejuvenation Pruning

If you’ve ever had an older common lilac in your landscape that went unpruned for many years, you’re probably familiar with their overgrown, unruly habit when left alone. Many people mistakenly believe that these shrubs have stopped flowering at this point. Oftentimes what’s actually happening is the flowers are being produced on just the upper portions of the shrub where the plant has reached a taller height and is exposed to sunlight. Once they’ve reached this stage, we’re often left to stare at bare, woody branches at eye level and below. For these overgrown shrubs, we can remove entire older canes or stems that are 2” in diameter or larger to encourage a rejuvenation of the shrub. We want to apply the rule of thirds when doing this type of pruning - Remove approximately one third of the older canes or stems each year for 3 years. This gives the shrub a chance to slowly transition back to a fuller, shorter shrub with more new growth filling in from the bottom. If you decide to drastically prune the entire shrub this way all at once rather than just a third of it, a little extra care like fertilization and watering will be important to encourage new growth. Note that this “all at once” approach is generally not recommended for the health of the shrub.

Your lilac flowers can be influenced by many things, including the temperature, soil conditions, even disease and insect problems, but proper pruning goes a long way to ensuring they put on a great show every spring. And remember, if you have specific questions about pruning or anything tree and shrub related, your dedicated Russell Tree Experts arborist is only an email or phone call away.

*New* Video!

To accompany the above article, Walter Reins demos how to prune lilac trees in this new video! Click below!

Please note: This article was originally published on 4/6/2020 and was republished on 3/6/2025.

ADDITIONAL ARBOR ED ARTICLES!

Walter Reins | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Walter became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2003 and has a degree in landscape horticulture. He has 25 years of experience in the tree and landscape industries and originally began working at Russell Tree Experts in 2011. Walter is also the owner/operator of Iwakura Japanese Gardens, a small design/build/maintenance firm specializing in Japanese-style gardens, and also offers responsible tree planting for all landscapes.

Bend So You Don’t Break

Last summer, I had the opportunity to introduce our field staff to the practice of yoga. In heavy work boots and on a hard concrete floor, we made our way through Triangle Pose, Downward Facing Dog, and even a few Sun Salutations. Practicing yoga for 20 years and teaching it for the last 10, I’ve learned that the stretches and postures of yoga can help keep the joints and soft tissues of our body, like muscles and tendons, healthy and functional.

Last summer, I had the opportunity to introduce our field staff to the practice of yoga. In heavy work boots and on a hard concrete floor, we made our way through Triangle Pose, Downward Facing Dog, and even a few Sun Salutations. Practicing yoga for 20 years and teaching it for the last 10, I’ve learned that the stretches and postures of yoga can help keep the joints and soft tissues of our body, like muscles and tendons, healthy and functional. Tree care consists of many tasks that are demanding on the physical body, and yoga is a great way to address tightness in areas like the neck and shoulders, hips and lower back, and even the hands and wrists. This can lead to greater mobility and functional movement when lifting heavy wood or climbing a tree. We now have a regular morning yoga practice at Russell Tree Experts(with mats!), every Tuesday and Thursday before the crews begin their day. Even our mechanics and office staff join in.

This combination of yoga and trees got me thinking back to a significant winter earlier in my career as an arborist. On December 22nd, 2004, Columbus was hit with a nasty winter storm. I was living far enough north of the city at the time that I saw nothing but snow at my home. Columbus, however, received a devastating combination of snow and ice. I was an ill-equipped new homeowner, so after hand-shoveling my 350ft gravel driveway (oh, to be 23 again…), I made my way to work and was in disbelief over what I saw. Because of the heavy ice accumulation, there were trees and limbs down in practically every yard. Many white pines and siberian elms had literally been stripped of every limb and left to look like totems or coat racks. There were also river birch and arborvitae bent over so much (but not broken) that their tops were touching and frozen to the ground. What is typically a slower time of year in the tree care industry proved to be very busy, and day after day of cleanup carried us straight into spring.

That winter provided me with valuable insight into the strengths and weaknesses of trees. Some types of trees with stiffer wood fibers didn’t fare as well, while others that had the ability to bend, but not break, held up much better under heavy loads. Many of those river birch and arborvitae that I mentioned righted themselves by mid-spring and were able to be preserved.

So what does all of this have to do with proper tree care? We obviously cannot change the inherent nature of a tree’s wood fibers and make them bend more or bend less. Nor can we prevent major weather events. But, we can proactively address existing weaknesses in a tree, and we can also ensure that pruning is performed properly, so as not to create a vulnerability that otherwise wouldn't have existed. Just like yoga can help us avoid injury or illness by keeping our bodies flexible and healthy, proper tree care can do the same for our trees. Here are a few examples:

Removing large cracked/broken limbs

These limbs are obvious hazards to targets like homes and pedestrians if they fall out of the tree, but they can also do additional damage to the tree itself. A structurally unsound limb, if left in the tree, can place unwanted stress on otherwise healthy limbs if it breaks but doesn’t fall out completely. Eliminating these defective parts of a tree allows the rest of the canopy to structurally function at its best.

Making proper pruning cuts

When pruning cuts are made correctly, a healthy tree will compartmentalize and attempt to close off the wound that was created. This helps to prevent decay of the woody portion of a limb or trunk that gives a tree its strength. Improper cuts don’t close up correctly and can become areas where decay eventually spreads into the tree. This greatly increases the risk of failure or breaking when forces like wind or ice act upon that part of the tree.

Avoiding “Lion’s Tailing”

This is a term used to describe the improper pruning of a tree where all the lateral branches have been removed from the larger limbs, leaving each of those limbs with brush only at the ends and looking like “lion’s tails”. Aside from aesthetically ruining a tree, this improper method of pruning can actually concentrate forces like wind or added weight at the point of attachment, rather than distributing it throughout the length of the limb. In high winds especially, this can lead to an increased risk of failure.

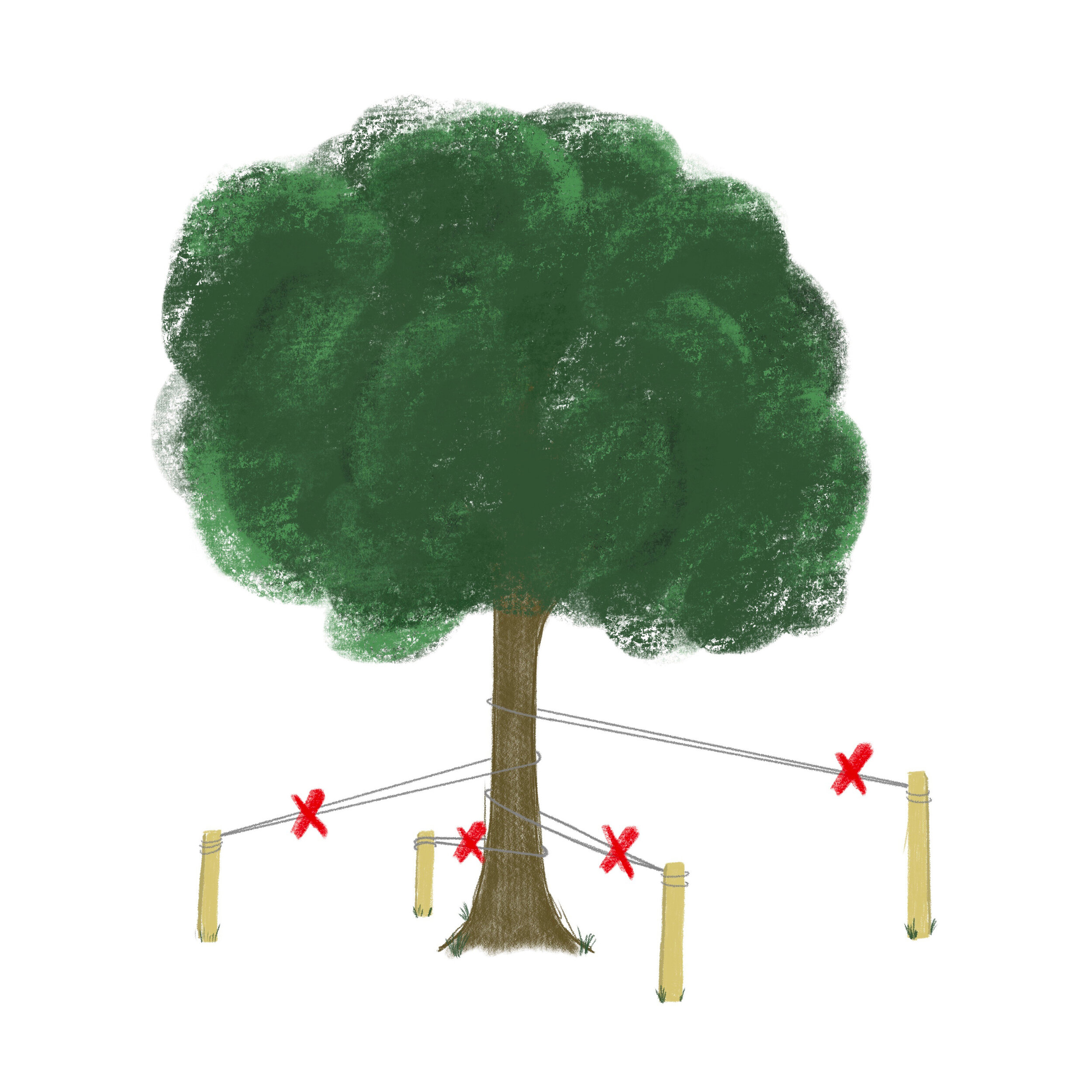

Minimize staking of new trees

This one has more to do with proper tree planting than it does with proper care of established trees, but it’s worthy of mentioning. Young trees will actually develop stronger roots and wood fibers in response to forces placed upon them. A newly planted tree needs to get “thrown around” a bit in the wind in order to properly establish and “bend” with future stressors rather than “break”(or blow over in this case). Staking a tree, especially beyond the first year, provides an artificial system of support that the tree will come to rely on for as long as it’s in place. Think of it as “tough love” for young trees.

These are just a few key examples of how proper tree care gives our trees a chance to thrive, adding function and value to our landscapes. Prevention is the best medicine - we know this to be true for ourselves, and it’s equally true for our trees.

Were you in Columbus for the winter ice storm of 2004? Leave your stories and experiences of that winter in the comments below. Or do you have a yoga practice and appreciate the strength that comes with flexibility? Share your thoughts with us.

For now, I’m going to work on getting my Oak to try something other than Tree Pose.

Walter Reins | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Walter has been an ISA Certified Arborist since 2003. He graduated from Montgomery College in Maryland with a degree in Landscape Horticulture, and has called Columbus, OH his home for nearly 20 years. Walter appreciates trees for their majesty and the critical role they play in our world.

Growing Degree Days

This semester I am enrolled in a class called Integrated Pest Management, taught by Dr. Luis Cañas at The Ohio State University. One of the first lectures we had was centered around the effects that the environment has on insect populations. As we explored this theme we soon came across the concept of “growing degree days”, and I was reminded of how useful this idea is to increase awareness of what is happening in the natural world around us and to be aware of when potentially damaging insect pests are about to emerge.

This semester I am enrolled in a class called Integrated Pest Management, taught by Dr. Luis Cañas at The Ohio State University. One of the first lectures we had was centered around the effects that the environment has on insect populations. As we explored this theme we soon came across the concept of “growing degree days”, and I was reminded of how useful this idea is to increase awareness of what is happening in the natural world around us and to be aware of when potentially damaging insect pests are about to emerge.

Reminded? Yes. At Russell Tree Experts we have been using growing degree days for years now as a tool to help when scheduling our tree wellness services. Seeing the concept again in class made me want to share it with all interested readers.

The concept of growing degree days is based on three basic principles which I will draw from my lecture notes provided by Dr. Cañas:

A “degree day” is the term used for the amount of heat accumulated above a specified base temperature within a 24-hour period.

The base temperature is (ideally) also the “lower temperature threshold”, which is the temperature below which a certain insect will not grow or develop. This is determined by research.

“Cumulative degree days” are just that: the number of degree days that have built up since a certain starting point (in general, since the beginning of the year).

What does this mean for living creatures? This is where things get interesting, so I’m glad you’ve read this far. Have you ever wondered how an insect knows it is time to hatch, or lay eggs, or go into pupation, or finish pupation so it can emerge as an adult? Is it increasing hours of daytime as days get longer after winter? (Maybe, but not quite directly). Is there some sort of internal clock that is ticking that just tells insects when to go into the next stage of development or propagation? But what if that clock went out of sync with environmental conditions? If you are reading this, you are very likely in central Ohio. Lovely state that it is, what do all Buckeyes say about the weather in our state? Exactly. Case in point: Here I am on Monday, February the 3rd, and today I was taking off clothes since I dressed for winter in the morning and got ambushed by 60 degrees and sunny. But the forecast looks like snow by Wednesday.

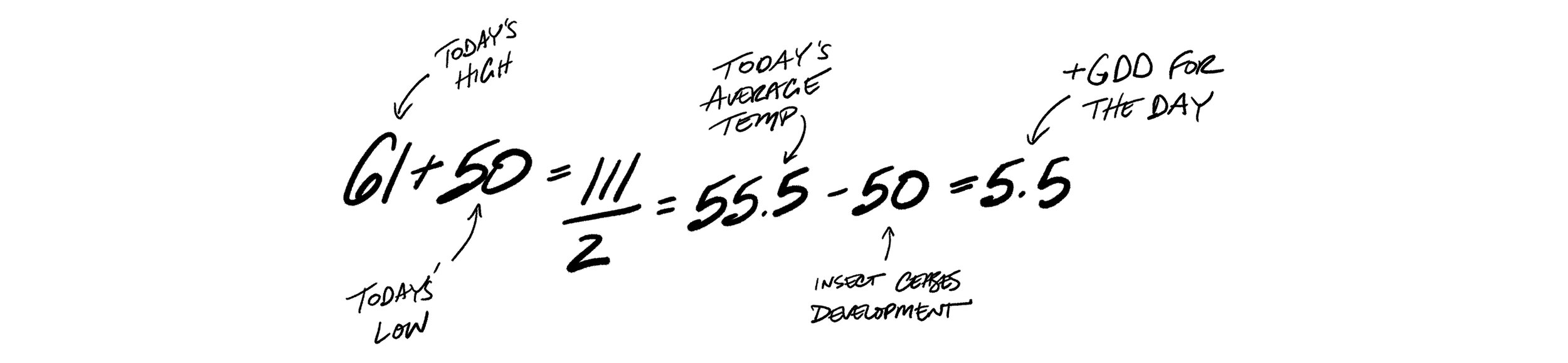

So what is it? Well, people devoted to these questions looked into it and found that apparently it is the accumulation of heat over time that causes insect development to proceed in synchrony with environmental conditions. So for a given insect, development will begin and continue above a certain temperature (low temperature threshold). Once so many degree days have accumulated (again, specific to the insect type), an egg will hatch, or an adult will emerge, or a nymph will grow into a more advanced stage, for example. These numbers can be identified for insects by watching and measuring. One simple formula (there are others that are more complicated) for tracking degree days is like this:

Starting on January 1st, the low temperature and the high temperature within that 24-hour period are logged. Those two temperatures are averaged, and the base temperature (low temperature threshold) is subtracted from the total.

For example: The high today was 61. The low was 50. 61+50= 111. 111/2 = 55.5, the average temperature. Let’s assume a certain insect, we can call it “Steve”, ceases all development when temperatures drop below 50 degrees. We would subtract 50 from 55.5, resulting in 5.5 degree days for today, February 3rd. Note that this number is only accurate for my specific area, since highs and lows are different throughout the state. This is another advantage of this system: It allows us to track Steve’s development in our own back yard!

Continuing with our friend, research has shown that Steve will emerge from pupation as a feeding adult after the accumulation of say, 548 cumulative degree days. What we would do is track degree days every day until we reach at least 548. After we reach that amount we would expect to start seeing Steves show up in our back yard on whatever plants Steves like to hang out on, doing whatever it is Steves like to do when they show up. The neat thing about this is that if we have a cold snap that lasts 3 weeks, even after two days of t-shirt weather in February (which is quite normal for Ohio right?), Steve’s development will simply pause, since degree day accumulation will slow down dramatically during the cold snap. Any day that there is at least 1 degree day, Steve will continue to develop, albeit much more slowly than if there were 20 degree days added on a given calendar date.

If you take the time to think this through you will start to connect all kinds of dots together that will make you marvel at the intricacy of our natural world, and how interconnected everything is. Nothing short of miraculous.

We’re almost done. One more tidbit: Plants seem to follow a similar pattern. This is not only neat, but useful! Since plants also follow this pattern it is only to be expected that certain plants will be at certain stages in their development each spring when Steve is at certain stages of his development each spring. So let’s say it just so happens that my Purple Robe Black Locust is starting to get all dressed up in her pink party dress at around 548 cumulative growing degree days, and that just happens to be the same amount of degree days that Steve needs to finish pupating and emerge as an adult. Instead of calculating degree days to watch for Steve, I can simply keep my eyes on my flowering tree. When I see her in full bloom I know that Steve is also out and about. In this case we call my Black Locust a “phenological indicator”. Her blooming is an outward sign of development in a plant that coincides with an important stage of insect development, thus serving as an indicator for that insect life stage.

The Ohio State University is full of very hard working citizens who study these things. Not only that, they track these things for us and give us a handy tool that does all the calculations (more complex versions than the basic one I shared) and tabulates events at the same time. Check out the resource here: https://www.oardc.ohio-state.edu/gdd/. Delve into it a bit. If you did not know about degree days and how they affect plants and insects, you will be amazed, if you are interested in the outdoors. If you already knew about these things before reading this article, I hope reading this made the concept a bit more accessible. Maybe now you can readily expound on the topic at the next ice cream social you are invited to. Be careful though- you would not want it to be your last. In any case, I am fairly certain you will not find a Steve on the OSU website I gave you above. Steves are not considered to be plant or tree pests so they have not been studied by our worthy scientists.

As always, thank you for reading. I am humbled by all the support I get from my readers. I have had the pleasure of conversing with many of you over the years and count myself blessed because of it.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

Identifying & Managing Rhizosphaera Needle Cast

Rhizosphaera needle cast (RNC) – quite a mouthful, especially when one is an arborist in training, still green in the green industry. My supervisor had just handed me a photocopy of a fact sheet on the disease since I had asked him about spruce trees I had been seeing with defoliating branches.

Rhizosphaera Needle Cast

By José Fernández

Rhizosphaera needle cast (RNC) – quite a mouthful, especially when one is an arborist in training, still green in the green industry. My supervisor had just handed me a photocopy of a fact sheet on the disease since I had asked him about spruce trees I had been seeing with defoliating branches.

This took place early in my career, 14 years ago or so, here in central Ohio. Fast forward to the present when the disease has become so prevalent that news stories on local television and in local papers have covered the issue. For several years my colleagues at Russell Tree Experts and I have discussed the need for a short article about this since we have this conversation so often with clients, but we never have made a point to write one! So much to do in so little time. I think I run into declining spruce trees with this disease 3-5 times per week so I know there are many readers who will benefit from this topic, or know someone who will.

Colorado spruce (Picea pungens) is a species that is probably overused due to its attractive evergreen foliage. In particular, the “Blue” varieties (‘Glauca’, ‘Hoopsii’, among others) seem to be the most popular, used as accent plants where they really stand out against a larger backdrop of more traditional green foliage. Interestingly, a quick check of the literature does not show that the species is prone to very serious disease, even though needle cast disease is mentioned as a possibility.

Young Colorado spruce rapidly defoliating

This is the reason why I seem to have suddenly shifted from one topic (RNC) to another (Colorado spruce). The tree is widely used (and therefore widely available) yet there is not a lot of information about how the species is performing in central Ohio. Please keep in mind that as an arborist I am trained to consider long term performance of a tree as opposed to short term. This means that I view trees as potentially permanent part of the landscape that we can choose to work around when subsequent changes in site use or design are necessary. This view is not shared by all, and my purpose here is not to defend my position against others. I mention this because Colorado spruce may still be a great choice of tree if its purpose is short-lived by design. I find that most individuals who plant trees do so because they treasure the feeling of starting a living process that will continue long after they are gone from this life. I am in this category, and I derive great benefit from seeing a tree remain healthy as it grows, changing and maturing. I help the tree along and it becomes a living, contributing part of my local environment.

I have come to believe that Colorado spruce is not a good option for a long term investment of resources (time, space, money). I would guess that about 90% of these trees eventually develop RNC to an extent that makes removal necessary as symptoms progress, causing the tree to lose its needles prematurely.

Fungal fruiting bodies

RNC is caused by a fungal pathogen. The fungus reproduces by forming spores in fruiting bodies (see photo above) that grow in the leaf stomata (openings in the leaf or needle, usually on the underside, that allow for gas exchange with the environment). Because of this, one diagnostic tool is to look for small black fruiting bodies lined up nicely on the underside of a spruce needle. Usually the stomata are white, which makes fungal fruiting bodies stand out when they are present. The spores spread with wind or rain, moving into the tree. In the case of RNC, disease symptoms soon follow, usually marked by needles that first turn a purplish color, then brown (see photo below), then dropping.

Purplish brown needles

The defoliation pattern will be from the inside of the tree moving outward, and generally from the bottom of the tree moving upward, although sometimes it can move downward as well. Cool, moist conditions will favor the development of most fungal diseases, including RNC. Hosts of this pathogen include most spruce, several pine, and some fir and hemlock species. I have found several Norway spruce with RNC, but generally I consider this tree to be resistant consistent with the literature. To my knowledge I have not seen this disease on any pine or hemlock, although the early disease symptoms present differently and I may have missed it. For example, in Norway spruce the browning pattern is preceded by a mottled yellowing of the needles rather than the purplish color seen in Colorado spruce. The “fall color” (see photo below) of Norway Spruce can be confused with needle cast symptoms.

Normal needle cycling “fall color” of Norway Spruce

To differentiate between the two, the diagnostician should look for the fungal fruiting bodies and evaluate the pattern and extent of needle loss in the tree. I still heartily recommend Norway spruce as a good option for us in central Ohio, but for several years now have discouraged people from planting Colorado spruce simply because I am either removing them, waiting to remove them, or spraying them with fungicides.

Fungicide sprays for this disease are mostly protectant rather than curative. For this reason multiple applications are recommended each season, with the goal of providing a chemical barrier over newly emerging needles as growth occurs each spring. Once past the cool, moist spring conditions the needles harden off, climate gets warmer and drier, and infection is less likely, but still a possibility. One of my colleagues visited Colorado a few years ago. When he returned he said two things to me: “There are still streets with ash trees in Colorado, and the spruces don’t have needle cast”. Why do our Colorado spruce get needle cast? Our climate is much warmer, much more humid. Our soil tends to be poorly drained, and alkaline. Bring a tree genetically adapted to a specific environment into a different environment and it will likely become stressed, making it vulnerable to disease. In central Ohio, I have seen a trend with Colorado spruce: The trees look great when they are newly planted. If the site is very poor, they quickly develop RNC or decline for other reasons. If the site is reasonable, the trees grow very well and remain beautiful. Then we get to that 90% mark I mentioned earlier, which seems to be with trees that have done reasonably well for 15-25 years, but now have entered into rapid, noticeable decline resulting in tree death within 10 years. Most people choose to have the trees removed well before the trees are completely dead since they lose their beauty and no longer serve as screening plants. This is why I consider this species to be useful if the intended design is only for the next 15 years or so.

If you have a Colorado spruce you want to preserve here are some things that will help:

I recommend repeat applications of fungicides on a seasonal basis to protect newly emerging needles. Note that this does not guarantee that your tree(s) will remain disease free, but it will greatly reduce the infection rate.

Change any existing irrigation so that water is not being sprayed onto the tree foliage. Water the tree with drip irrigation at the base.

Weeds and neighboring plants should be kept away from the lower foliage to increase sunlight and air penetration to try to reduce moisture and humidity levels.

You may consider enjoying your Colorado spruce (whether a green or blue variety) for as long as it looks good, but plant some replacement trees nearby to get them started now. Concolor fir is an evergreen tree that has a bluish cast to it and will perform well given well drained, biologically active soil. Norway Spruce is a good option if the space requirements are met, as this tree will grow large. Western redcedar is proving to be a top performing tree for us, and is also a good screening evergreen plant.

In closing, it is worth mentioning that the dwarf forms of Colorado spruce, whether blue or not, seem highly resistant to RNC. I rarely see this disease on the dwarf varieties.

Thank you for reading! My sincere hope is that this information is useful to you.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

Humid Air: Tough for Plants and People

Summer in central Ohio brings good times outside but also often brings hot humid air. Heat and humidity can aggravate some foliar fungal disease on trees and shrubs. One of the most common diseases we see is rhizosphaera needle cast on Blue Spruce trees.

Summer in central Ohio brings good times outside but also often brings hot humid air. Heat and humidity can aggravate some foliar fungal disease on trees and shrubs. One of the most common diseases we see is rhizosphaera needle cast on Blue Spruce trees.

This disease manifests itself in needles causing them to turn brown and even purplish before they fall off of the tree. Blue Spruce will often show the first signs of infection on the interior and lower needles where moisture persists, looking thinner and sickly in the middle during the early years of an infestation. Left to run wild without a managment plan, rhizosphaera needle cast will eventually kill its host tree.

Blue Spruce without (left) and with (right) rhizosphaera needle cast

If you have a mature Blue Spruce that has lost less than approx. 25-35% of its needles from needle cast, a treatment plan may include:

Raking up and disposing of all of the old fallen needles under the tree that can still host the fungal spores.

Pruning out dead branches.

Adjust irrigation equipment to make sure that water is not directly sprayed onto the needles of the tree, this spreads the spores and accelerates the advancement of needle cast.

Three rounds of fungicides applied in the spring, shortly after bud break can protect new growth from becoming infected.

Joe Russell | Member & Co-Owner, Russell Tree Experts

Joe Russell has been an ISA Certified Arborist® since 2003. He graduated from Ohio State University with his bachelors in Landscape Horticulture with a minor in Ag Business and started Russell Tree Experts with his wife Shari in 2005. Joe grew up in the Ohio Valley near Wellsville, Ohio and is a resident of Galena, Ohio.

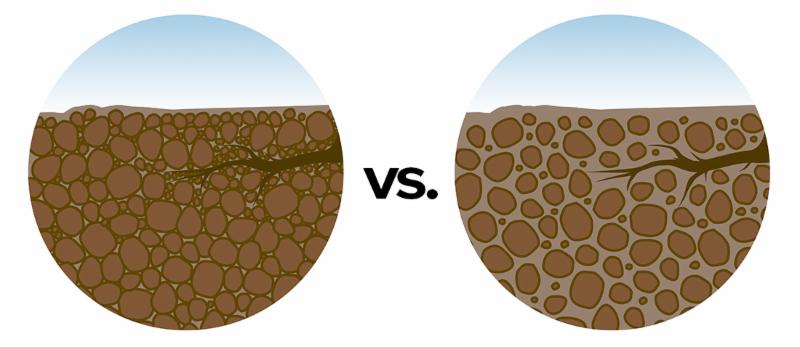

Soil Compaction = Not Good for Trees

Soil compaction is a big no-no for trees. When soil is compacted (above left graphic), water and oxygen cannot get to the vital root system of the tree. Water will collect on the surface and evaporate since it is unable to penetrate the soil. Seeing as trees need water and oxygen to live, compacted soil can quickly and severely impact the health of a tree.

Soil compaction is a big no-no for trees. When soil is compacted (above left graphic), water and oxygen cannot get to the vital root system of the tree. Water will collect on the surface and evaporate since it is unable to penetrate the soil. Seeing as trees need water and oxygen to live, compacted soil can quickly and severely impact the health of a tree.

DID YOU KNOW?

80% of a tree’s absorption roots are in the top 12” of the soil. That is way soil compaction is so detrimental to a tree’s health.

AirSpade in Action

To treat this issue we often recommend a Root Zone Invigoration which is performed by using a supersonic air tilling tool (called an AirSpade) that infuses organic matter into the soil and alleviates compaction around mature trees and shrubs. The result (above right graphic) is a greatly improved environment for your trees to thrive - beautifully tilled soil with all critical fibrous roots still intact.

Check out the below animations which illustrate how water interacts with soil before and after a Root Zone Invigoration:

BEFORE

AFTER

Kenny Greer | Marketing Director, Russell Tree Experts

Kenny graduated from The Ohio State University with a BFA in Photography. He enjoys photography, graphic design, improv comedy, movies (except for the scary ones), and spending time with his wife and 2 kids.

New Research: Boxwood Blight Update

If you read my first installment on this relatively new disease, you will know the major difficulty of this pathogen (Calonectria pseudonaviculata) is that it infects otherwise healthy plants, and once it is at a site, removal and destruction of the infected plants is recommended, with no plant replacement for 3-5 years. This is because the spores remain in and on the soil to infect new plants. Existing asymptomatic plants were to be sprayed with fungicides to help prevent infection.

Boxwood Blight Update

By José Fernández

If you have boxwood plants, please read the following!

Last week I read an article about a new research project that tested the hypothesis that use of mulch may reduce the incidence of boxwood blight at previously infected sites.

Close-up of a boxwood (click to enlarge photo)

If you read my first installment on this relatively new disease, you will know the major difficulty of this pathogen (Calonectria pseudonaviculata) is that it infects otherwise healthy plants, and once it is at a site, removal and destruction of the infected plants is recommended, with no plant replacement for 3-5 years. This is because the spores remain in and on the soil to infect new plants. Existing asymptomatic plants were to be sprayed with fungicides to help prevent infection.

In this new study, two sites (field planting site and existing residential landscape site) were used to test the mulching hypothesis. The results at the residential site were particularly encouraging. At this site, infected plants were cut down, leaving stumps at around 15 cm in height (5.9 inches), similar to a rejuvenation or coppicing pruning. The pruned material was destroyed, but the stumps were freshly mulched to a depth of 8-10 cm (3-4 inches) in an area 2 x 2 m around the stump. Result? Complete protection (no infection) was observed the first season, and “excellent” protection the following season (low infection rate).

The authors of the study stated that the pathogen “primarily attacks leaves and stems”, and “there is no evidence to date of natural infection of boxwood roots” by this pathogen in the soil. Based on this information, recommendations for managing this disease will be summarized by the following steps, representing an integrated approach:

Above all else, do not allow new boxwood plants onto your property that are not guaranteed to be free of this pathogen by the supplier.

Any person/company working on your boxwoods must be able to guarantee that all equipment being used on the property has been cleaned and disinfected prior to entering your property to do work. Under no circumstances should debris from other properties be allowed to enter your property.

If a plant is deemed to have boxwood blight, remove the plant (bagged and dumped in trash or burned), clean away surface mulch and leaf litter, and add new mulch around the stump, periodically checking to maintain at about 3” in depth.

Remaining healthy plants should be put onto a fungicide spray program to provide topical protection for the next several seasons. Hopefully the coppiced plants will sprout vigorously and remain uninfected.

Surface irrigation (sprinklers) should be avoided near boxwood, since water splashing is one of the primary ways the spores are spread. Also, there is a positive correlation between inoculation rates and length of time foliage remains wet.

Exclusion of the pathogen will be the most important step in this program, and the more people become aware of this, the less the disease will be able to spread. Exclusion is maintained by the first two steps shown above. The mulching depth is rather more than normally recommended for plant health, but in this case the idea is to keep fungal spores from landing on stems and leaves.

Please pass this information along to anyone you know that has boxwood plants. The more people we have following exclusion principles, the less this disease will be able to spread.

Reference: Likins, T. M., Kong, P., Avenot, H. F., Marine, S. C., Baudoin, A., and Hong, C. X. 2018. Preventing soil inoculum of Calonectria pseudonaviculata from splashing onto healthy boxwood foliage by mulching. Plant Dis. 103: 357-363.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

That "Stuff" Growing on Bark

As Central Ohio moves further into winter, and the majority of deciduous trees have dropped their leaves, bark becomes increasingly visible. Bark is an interesting and important characteristic for trees and tree identification. It doesn’t take long for a novice naturalist to distinguish certain tree species based almost entirely on the bark of a specimen (Beech, Hackberry, River Birch, etc.). Upon further inspection of a tree’s bark an observer might notice organisms growing on the trees bark. A large variety of fungi can be seen on the bark of deadwood in trees and is usually associated with poor health of that particular branch or the entire tree. However, fungi are not the only organism to inhabit the bark of trees.

That “stuff” growing on bark

by ISA Certified Arborist® Chris Gill

As Central Ohio moves further into winter, and the majority of deciduous trees have dropped their leaves, bark becomes increasingly visible. Bark is an interesting and important characteristic for trees and tree identification. It doesn’t take long for a novice naturalist to distinguish certain tree species based almost entirely on the bark of a specimen (Beech, Hackberry, River Birch, etc.). Upon further inspection of a tree’s bark an observer might notice organisms growing on the trees bark. A large variety of fungi can be seen on the bark of deadwood in trees and is usually associated with poor health of that particular branch or the entire tree. However, fungi are not the only organisms to inhabit the bark of trees.

Lichen (pronounced “Like-N”) is frequently seen on trees in Central Ohio and is often mistaken as a sign of a tree’s poor health. Lichen is the result of at least two different organisms living in a symbiotic relationship on the exterior of a tree’s bark. This symbiotic relationship usually consists of a fungus and green alga and/or a cyanobacterium with the filaments of the fungus making up the majority of the lichen. Lichen do not have the typical plant parts (roots, stems, leaves, cuticle, etc..) but instead attach themselves to the outer layer of a trees bark with rhizines. The rhizines are tiny hair like structures that do not penetrate into the inner bark and are harmless to the tree. The Lichen is able to photosynthesize its own food and gather moisture from the air, fog, dew drip or rain. In the vast majority of cases the lichen and tree relationship is viewed as being one of “commensalism,” where the Lichen benefit from the tree with the tree neither benefiting nor being adversely impacted by the Lichen. Lichen benefit from attaching itself to the bark of trees due to the increased availability of sunlight and it is this need for sunlight that makes Lichen really thrive on dead trees (no leaves, more light). The casual observer might infer that the cause of death was due to the Lichen; however, it’s just lichen taking advantage of the sunlight provided by the dead tree.

Lichen are an interesting organism and can grow even in the most extreme conditions. Next time you find yourself looking at a tree, keep your eye out for lichen!

Chris Gill | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

ISA Certified Arborist® OH-6416A // Tree Risk Assessment Qualified (TRAQ) // ODA COMM. PESTICIDE LIC. #104040 // Russell Tree Experts Arborist Since 2015

A Boxwood Bummer

I wanted to dedicate this installment to Boxwood Blight, since this is a disease which has the potential to disrupt formal landscapes all across the state. The disease is fungal, and affects boxwood, especially the cultivated varieties ‘American’ and ‘Suffruticosa’. It is relatively recent in the United States, and was found in Ohio nurseries in 2011.

I wanted to dedicate this installment to Boxwood Blight, since this is a disease which has the potential to disrupt formal landscapes all across the state. The disease is fungal, and affects boxwood, especially the cultivated varieties ‘American’ and ‘Suffruticosa’. It is relatively recent in the United States, and was found in Ohio nurseries in 2011. The Ohio State University has been expecting this disease to crop up in residential landscapes, and now is beginning to see this happen. The disease is a new one for me, and I have not personally found it in any of my landscape inspections. To date, Russell Tree Experts has not applied any fungicide preventively for this issue, but we will have a plan in place for the 2019 season. My main goal in writing this article is to begin to raise awareness about this serious disease, and that it is out there.

Boxwood is a plant that many would consider to be overused in landscape design, but perhaps this is because few plants offer the characteristics that Boxwood does. It is evergreen, takes shearing well, and comes in many sizes and forms. Therefore this plant is an exceptional choice for hedges, both formal and informal, for screening or for outlining borders in a garden or landscape. The difficulty with hedges, or with mass plantings of any size, is that the loss of one plant is much more significant than in an informal grouping of trees or plants of varying species where the loss of 1-2 single plants goes unnoticed.

Years ago I helped take care of the landscape at a large private residence that had many formal plantings incorporated into its design, along with less formal groupings of trees. My stress levels were much higher when one of the formal tree arrangements was threatened by the loss of a single tree. Imagine a formal circle of mature shade trees missing one of its members due to disease or storm damage. The effect is similar to missing one tooth out of an otherwise healthy smile. Somehow the overall result of a missing tooth is not helped by the fact that there are 31 other teeth still remaining. And replacing a mature tree to fill in the gap is arguably much more difficult than replacing a missing tooth.

This is the effect Boxwood Blight could have on many, many landscapes we serve. I imagine that 8 out of 10 readers have at least one row of boxwoods somewhere in their landscape. Some of you have massive formal plantings of hundreds of boxwoods. What makes this disease different than others that have been affecting boxwood for years?

In September of this year I attended the 2018 Urban Landscape Pest Management Workshop at The Ohio State University. There, Dr. Francesca Peduto Hand introduced me to this disease with several main points that raised concern:

The disease can infect otherwise healthy plants.

When climate conditions are favorable, the disease can progress very quickly.

Infected plants must be removed and destroyed, and it is not recommended that boxwood be replanted for 3-5 years from the time the last infected plant was removed.

This is like saying you have to pull the infected tooth, and you can’t get a new tooth implanted for 3-5 years. The best defense is knowing what the symptoms are:

First there are dark spots on leaf surface and white sporulation (fungal spores) on the underside of the leaf.

These spots spread on the leaf, eventually causing defoliation.

Black, elongated cankers are evident on defoliated stems.

Unfortunately, once symptoms are found, the plant must be destroyed. The best preventive measure is to make sure any new plants coming into the landscape from the nursery are carefully inspected and approved as symptom free.

Another preventive defense is a regimen of fungicide applications. These can be costly depending on the size of the hedge and the frequency of applications. Also consider that since the applications are preventive, they need to be repeated on a seasonal basis and would have to become part of a permanent landscape budget.

A pdf with good photos and symptom descriptions authored by the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station can be found here:

I leave you, dear reader, with the heartfelt wish that your landscape may remain disease free! May you draw nothing but pleasure and peace from the plants which surround you. Be wary of what may be hitching a ride into your landscape on new plants.

Your friendly neighborhood arborist,

José Fernández | Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

José became an ISA Certified Arborist® in 2004, and a Board-Certified Master Arborist® in 2015. Currently he is enrolled at The Ohio State University pursuing a Master’s Degree in Plant Health Management. José likes working around trees because he is still filled with wonder every time he walks in the woods. José has worked at Russell Tree Experts since 2012.

Don’t Get Fooled by the Fall Color of Conifers!

Every fall I get calls from folks concerned about yellow needles on their evergreen trees. Often times I’m told that the trees are sick or that they appear to be dying from the inside out. There are some disease and insect problems that can cause yellowing and premature loss of needles in conifers but most often what people are reporting is just normal fall color.

By TJ Nagel

ISA Board Certified Master Arborist® OH-6298B

November 13, 2025

Every fall I get calls from folks concerned about yellow needles on their evergreen trees. Often times I’m told that the trees are sick or that they appear to be dying from the inside out. There are some disease and insect problems that can cause yellowing and premature loss of needles in conifers but most often what people are reporting is just normal fall color.

Yellowing and the loss of old needles in the fall is normal for pine, spruce, arborvitae, hemlock and most evergreen conifers in the midwest. Most conifers shed their needles each year starting in late August and continue through November. Older interior needles will turn yellow while needles further out in the canopy and at the tips of branches will stay green. The yellow needles eventually drop off starting at the top of the tree and working their way to the bottom in a uniform fashion. Taxus (also called Yew) is the exception showing it’s “fall color” in mid to late spring.

Most folks understand and look forward to the fall color change in our maples, oaks, hickories and other hardwood trees — fall needle drop in conifers is as normal as leaf drop in deciduous trees.

The change in color and eventual drop of foliage is simply a physiological response to the shorter days and cooler temperatures as trees (both evergreen and deciduous) prepare themselves for the winter.

Pictured below are some of my favorite conifers showing fall color: